Harriette R. Mogul, MD, MPH

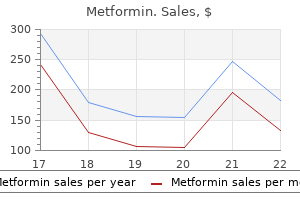

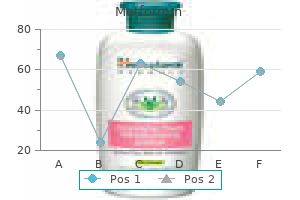

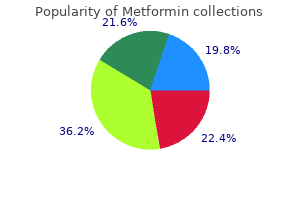

Several respondents commented on the gap in relevant international agriculture-sector disease data diabetes type 1 nutrition education order cheap metformin on line. This particular gap can be due to poor infrastructure and/or lack of appropriate incentives to report animal disease diabetes medicine himalaya order cheap metformin on line. The majority of respondents noted that agencies across the federal government need the same basic information blood glucose 550 buy discount metformin 850 mg online, and that several agencies have important information blood sugar 80 metformin 850mg, but that infor mation is not widely shared. For example, one oce reported that its secretary, a major stake holder, had to contact the director of national intelligence to ask for information after learning that the President was being briefed on a strategic global infectious disease issue without direct input from his department. Other shortcomings in currently available information include inadequate timeliness, accuracy, completeness, and larger contextual analysis. Several respondents commented that what is lacking is a resource to coordinate and consolidate public health and other information and share useful, common analytic products with stakeholders across government. For example, respondents from several government agencies noted that overseas-based U. One ocial in a regu latory agency would like information on domestic surge capacity needs, particularly as related to the medical supplies and equipment his agency regulates. Preferences Vary for Information-Delivery Format and Methods Nearly all respondents commented on the overwhelming amount of information and the need for eciency in obtaining desired information. Not surprisingly, the preferred format and presentation of information varied by both agency and the level of the individual within her or his agency. For example, those higher in the federal structure tended to prefer ltered or processed information presented as con cise analysis products, including daily or weekly summaries of a single disease or a handful of key diseases. Tose responsible for preparing briengs and papers for senior ocials need more detailed information, including basic disease information and reports on the status of an ongoing outbreak, preferably based on validated case reports. Stakeholders Suggested Areas for Improvement Virtually all respondents oered suggestions and insights for improving global infectious dis ease information. They generally framed their suggestions to address both bioterrorism and naturally occurring disease threats, easing what some viewed as disproportionate attention to deliberate threats at the expense of more likely threat scenarios. A common suggestion was for improved detection capacity and timeliness and transparency of disease reporting by for eign governments. However, these are not necessarily within the direct purview of the United States. At least two respondents called upon the United States to invest more in the disease surveillance activities of foreign governments. This would serve the dual purpose of helping to strengthen foreign public health infrastructures for the collective good and providing oppor tunities for more U. One State Department ocial also described his plans for taking fuller advantage of embassy sta and the U. In contrast, two individuals from the intelligence community commented that the current era of global communications limits the need for additional U. Several respondents commented on the need for dierent government agencies to understand and interact more fruitfully with one another. One interviewee noted that there might not be sucient focus on health at the highest levels in the U. Most current federal employees we interviewed oered one or more specic sugges tions for a centralized, time-sensitive. Several respondents commented that they would welcome a multilateral or philanthropic initiative to collect, integrate, coordinate, and actively disseminate open-source information on infectious disease threats worldwide. Summary Tere is now an impressively broad range of government stakeholders interested in informa tion on worldwide infectious disease threats. As noted in Chapter Tree, health professionals increasingly recognize the broader social, economic, and political impact of these diseases, and ocials in other sectors and agencies increasingly appreciate the transition of infectious dis eases and public health into the realm of high politics. Dening Information Needs: Interviews with Stakeholders 37 and to other stakeholders as possible, including U. The preceding chapter summarized the views of stakeholders regarding current information sources and ideas for improvements. In this chapter, we describe a more systematic assessment of currently available information. Terefore, while not purporting to have captured all such sources, we encompassed a number and range of online sources that is sucient to both assess the nature of current online information and serve as a potentially useful resource for U. A comprehensive analysis of the content or quality of these sources was beyond the scope of this project. This chapter describes our methods and the detailed descriptive analyses of the key characteristics of these sources, based on our survey. The sources we compiled focused predominately on human diseases but also included animal and plant diseases relevant to human health. We reviewed all potential online sources to ascertain accessibility and content directly relevant to the public health aspects of infectious diseases or useful in support of disease control. We retained sources that were both accessible (or could be described based on publicly available information online or in the lit erature, if the sources were accessible only via authorization or subscription) and that we con sidered suciently relevant, as described below. We extracted key information on each source and created a standardized database describing their features to enable analysis and to facilitate searches based on selected features. Following completion of the database, we distributed it on a test basis to interviewees who had expressed an interest in such a tool. We also tabulated the number of sources according to the various characteristics described above. Assessing the Adequacy of Current Information: A Survey of Online Sources 41 Results The remainder of this chapter summarizes key characteristics of these online sources. It is organized into the following sections: accessibility of information; organizational sponsorship; primary purpose, with further discussion of general and early warning surveillance sources; human and nonhuman disease sources; active and passive information collection; and infor mation dissemination. The remaining open-access sources have research (10 sources, 7 percent) or other primary functions (19 sources, 13 percent). Open-access sites include global (45 sources, 32 percent), regional (15 sources, 10 percent), or national infor mation, including U. The remaining 24 percent of these sources is evenly distributed across other primary functions (between two and four sources in each category). The 22 sources (9 percent) requiring a subscription serve various purposes, including reference (seven sources, 32 percent), antiterrorism (seven sources, 32 percent), surveillance (ve sources, 23 percent), or other purposes (three sources, 14 percent). Slightly more than three-fourths of subscription-based sources (17 sources, 77 percent) are sponsored by com mercial organizations, with professional and academic organizations sponsoring three (14 per cent) and foreign governments sponsoring two (9 percent) sources.

Quantifcation techniques (eg diabetic diet pdf purchase cheap metformin line, Kato Katz diabetes insipidus in pregnancy buy 850 mg metformin visa, Beaver direct smear blood sugar solution recipes cheap 850mg metformin amex, or Stoll egg-counting techniques) to determine the clinical signifcance of infection and the response to treatment may be available from state or reference laboratories diabetes prevention evidence cheap 850mg metformin with mastercard. Although data suggest that these drugs are safe in children younger than 2 years of age, the risks and benefts of therapy should be con sidered before administration. In 1-year-old children, the World Health Organization recommends reducing the albendazole dose to half of that given to older children and adults. Reexamination of stool specimens 2 weeks after therapy to deter mine whether worms have been eliminated is helpful for assessing response to therapy. Nutritional supplementation, including iron, is important when severe anemia is present. Treatment of all known infected people and screening of high-risk groups (ie, children and agricultural workers) in areas with endemic infection can help decrease environmental contamination. Wearing shoes may not be fully protective, because cutaneous exposure to hookworm larvae over the entire body surface of children could result in infection. Despite relatively rapid reinfection, periodic deworming treatments targeting preschool-aged and school-aged children have been advocated to prevent morbidity associated with heavy intestinal helminth infections. Three distinct genotypes have been described, although there are no data regarding antigenic variation or distinct serotypes. In temperate climates, seasonal clustering in the spring associated with increased transmission of other respiratory tract viruses has been reported. However, prolonged shedding of virus in respira tory tract secretions and in stool may occur after resolution of symptoms, particularly in immune-compromised hosts. Roseola is distin guished by the erythematous maculopapular rash, which appears once fever resolves and can last hours to days. Other neurologic manifestations that may accom pany primary infection include a bulging fontanelle and encephalopathy or encephalitis. Essentially all postnatally acquired primary infections in children are caused by variant B strains, except infections in some parts of Africa. Virus-specifc maternal antibody, which is present uniformly in the sera of infants at birth, provides transient partial protection. As the concentration of maternal antibody decreases during the frst year of life, the rate of infection increases rapidly, peaking between 6 and 24 months of age. A fourfold increase in serum antibody concentration alone does not necessarily indicate new infection. An increase in titer also may occur with reactivation and in association with other infections, especially other beta-herpesvirus infections. However, seroconversion from negative to positive in paired sera is good evi dence of recent primary infection. In regions with endemic disease, a primary infection syndrome in immu nocompetent children has been described, which consists of fever and a maculopapular rash, often accompanied by upper respiratory tract signs. In areas of Africa, the Amazon basin, Mediterranean, and Middle East with endemic disease, seroprevalence ranges from approximately 30% to 60%. Low rates of seroprevalence, generally less than 5%, have been reported in the United States, Northern and Central Europe, and most areas of Asia. Sexual transmission appears to be the major route of infection among men who have sex with men. Studies from areas with endemic infection have suggested transmission may occur by blood transfusion, but in the United States, such evidence is lacking. These serologic assays can detect both latent and lytic infection but are of limited use in the diagnosis and manage ment of acute clinical disease. In the 1 For a complete listing of current policy statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics regarding human immunodefciency virus and acquired immunodefciency syndrome, see aappolicy. Local symptoms develop secondary to an infammatory response as cell-mediated immunity is restored. Group M viruses are the most prevalent worldwide and comprise 8 genetic subtypes, or clades, known as A through H. Three principal genes (gag, pol, and env) encode the major structural and enzymatic proteins, and 6 acces sory genes regulate gene expression and aid in assembly and release of infectious viri ons. Although B-lymphocyte counts remain normal or somewhat increased, humoral immune dysfunction may precede or accompany cellular dysfunction. Increased serum immunoglobulin (Ig) concentrations of all isotypes, particularly IgG and IgA, are manifes tations of the humoral immune dysfunction, but they are not directed necessarily at spe cifc pathogens of childhood. Specifc humoral responses to antigens to which the patient previously has not been exposed usually are abnormal; later in disease, recall antibody responses, including responses to vaccine-associated antigens, are slow and diminish in magnitude. Latent virus persists in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and in cells of the brain, bone mar row, and genital tract even when plasma viral load is undetectable. Only blood, semen, cervicovaginal secretions, and human milk have been implicated epidemiologically in transmission of infection. Transmission has been documented after contact of nonin tact skin with blood-containing body fuids. Most mother-to-child transmission occurs intrapartum, with smaller proportions of transmission occurring in utero and postnatally through breastfeeding. The risk of mother-to-child transmis sion increases with each hour increase in the duration of rupture of membranes, and the duration of ruptured membranes should be considered when evaluating the need for special obstetric interventions. Cesarean delivery performed before onset of labor and before rupture of membranes has been shown to reduce mother-to-child intrapar tum transmission. Postnatal transmission to neonates and young infants occurs mainly through breast feeding. The introduction of complimentary foods should occur after 6 months of life, and breastfeeding should continue through 12 months of life. False positive test results occur in samples obtained from infants younger than 1 month of age. If testing is performed at birth, umbilical cord blood should not be used because of possible contamination with maternal blood. Results from rapid testing are available within 20 minutes; however, confrmatory Western blot analysis results may take 1 to 2 weeks in some settings. Data from both observational studies and clinical trials indi-2 cate that very early initiation of therapy reduces morbidity and mortality compared with starting treatment when clinically symptomatic or immune suppressed. Effective adminis tration of early therapy will maintain the viral load at low or undetectable concentrations and will reduce viral mutation and evolution. Prophylaxis should be reinstituted if the original cri teria for prophylaxis are reached again. Immunization Recommendations (also see Immunization in Special Clinical Circumstances, p 69, and Table 1. The suggested schedule for administration of these vaccines is provided in the recommended childhood and adolescent immunization schedule 1. Transmission of varicella vaccine virus from an immunocompetent host to a household contact is uncommon. Similar postex posure prophylaxis regimens have been recommended for children with moderate to severe immune compromise who previously have been immunized with varicella vaccine. In resource-limited countries where complete avoidance of breastfeeding (replacement feeding) often is not safe, exclusive breastfeed ing is associated with a lower risk of postnatal transmission than is mixed breastfeeding and formula feeding. It also is recommended that zidovudine be included in maternal regimens, though a woman already receiving treatment need not have her regimen changed if her viral load is suppressed. As noted previously, observational studies suggest that use of 1 For complete listing of current policy statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics regarding human immunodefciency virus and acquired immunodefciency syndrome, see aappolicy. Joint statement of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. If a woman becomes pregnant while virally suppressed on an efavirenz-containing regimen, an attempt should be made to change her regimen. Initiation of postexposure prophylaxis after the frst 48 hours of life is not likely to be effective in preventing transmission. Order genuine metformin on-line. Fat Head.

An accelerated dosing schedule is licensed for 1 hepatitis B vaccine (Engerix-B) diabetes in newfoundland dogs purchase cheapest metformin and metformin, during which the frst 3 doses are given at 0 diabetes leg sores cheap metformin 500mg fast delivery, 1 diabetes in dogs feeding purchase metformin with a mastercard, and 2 months diabetic drugs buy discount metformin on-line. This schedule may beneft travelers who have insuffcient time to complete a standard schedule before depar ture. If the accelerated schedule is used, a fourth dose should be given at least 6 months after the third dose (see Hepatitis B, p 369). Yellow fever vaccine, a live-attenuated virus vaccine, is required by some countries as a condition of entry, including travelers arriving from regions with endemic infection. The vaccine is available in the United States only in centers desig-1 nated by state health departments. Yellow fever occurs year-round predominantly in rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa and South America; in recent years, outbreaks have been reported, including in some urban areas. Although rare, yellow fever continues to be reported among unimmunized travelers and may be fatal. Prevention measures against yellow fever should include protection against mosquito bites (see Prevention of Mosquitoborne Infections, p 209) and immunization. Yellow fever vaccine rarely has been found to be associated with a risk of viscerotropic disease (mul tiple-organ system failure) and neurotropic disease (postvaccinal encephalitis). There is increased risk of adverse events in people of any age with thymic dysfunction and people older than 60 years of age. Whenever possible, immunization should be delayed until 9 months of age to minimize the risk of vaccine-associated encephalitis. People who cannot receive yellow fever vaccine because of contraindications should consider alternative itineraries or destinations. The whole-cell inactivated cholera vaccine no longer is produced in the United States. In such cases, a notation of vaccine contraindication should be suffcient to satisfy local requirements. Typhoid vaccine is recommended for travelers who may be exposed to con taminated food or water. Travelers should be reminded that typhoid immunization is not 100% effective, and typhoid fever still can occur; both vaccines protect 50% to 80% of recipients. Mefoquine or chloroquine may be administered simultaneously with oral Ty21a vaccine. Because the vaccine is not completely effcacious, typhoid immunization is not a substitute for careful selection of food and drink. Saudi Arabia requires a certifcate of immunization for pilgrims to Mecca or Medina during the Hajj. The 3-dose preexposure series is given by intramuscular injection (see Rabies, p 600). Travelers who have completed a 3-dose preexposure series or have received the full postexposure prophylaxis series do not require routine boosters, except after a likely rabies exposure. Periodic serum testing for rabies virus neutralizing antibody is not necessary for routine international travelers. In the tropics, transmission varies with monsoon rains and irrigation practices, and cases may occur year-round. Because the infuenza season is different in the northern and southern hemispheres and epidemic strains may differ, the antigenic composition of infuenza vaccines used in North America may be differ ent from those used in the southern hemisphere, and timing of administration may vary (see Infuenza, p 439). When travelers live or work among the general population of a coun try with a high prevalence of tuberculosis, the risk may be appreciably higher. Children returning to the United States who have signs or symptoms compatible with tuberculosis should be evaluated appro priately for tuberculosis disease. It may be prudent to perform a tuberculin skin test 8 to 12 weeks after return for children who spent 3 months or longer in a high-prevalence country. Prevention strategies for malaria are twofold: prevention of mosquito bites and use of antimalarial chemoprophylaxis. For recommendations on appropriate use of chemopro phylaxis, including recommendations for pregnant women, infants, and breastfeeding mothers, see Malaria (p 483). Prevention of mosquito bites will decrease the risk of malaria, dengue, chikungunya, and other mosquito-transmitted diseases (see Prevention of Mosquitoborne Infections, p 209). Packets of oral rehydration salts can be obtained before travel and are available in most pharmacies throughout the world, especially in developing countries where diarrheal diseases are most common. During international travel, families may want to carry an antimicrobial agent (eg, fuoroquinolone for people 16 years of age and older and azithro mycin for younger children) for treatment of signifcant diarrheal symptoms. Antimotility agents may be considered for older children and adolescents (see Escherichia coli Diarrhea, p 324) but should not be used if diarrhea is bloody or for patients with diarrhea attributable to Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, Clostridium diffcile, or Shigella species. Travelers should be aware of potential acquisition of respiratory tract viruses, includ ing novel strains of infuenza. They should be counseled on hand hygiene and avoidance of close contact with animals (dead or live). Swimming, water sports, and ecotourism around freshwater carry risks of acquisition of infections from environmental contamina tion. The highest-priority 1 agents for preparedness were designated category A, because they have a moderate to high potential for large-scale dissemination, cause high rates of mortality with potential for major public health effects, could cause public panic and social disruption, and require special action for public health preparedness. Organisms in category A cause anthrax, smallpox, plague, tularemia, botulism, and viral hemorrhagic fevers, including Ebola, Marburg, Lassa, Junin, and other related viruses. Category B agents are moderately easy to disseminate, cause moderate morbidity and low mortality rates, but still require enhanced diagnostic capacity and disease surveillance. Some examples of these agents include Coxiella burnetii (Q fever), Brucella species (brucellosis), Burkholderia mallei (glanders), Burkholderia pseudomallei (melioidosis), alphaviruses (Venezuelan equine, eastern equine, and western equine encephalitis), Rickettsia prowazekii (typhus), and toxins such as ricin toxin from Ricinus communis (castor beans) and Staphylococcus enterotoxin B. Additional category B agents that are foodborne or waterborne safety threats include, but are not limited to , Salmonella species, Shigella dysenteriae, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and Vibrio cholerae. Category C agents include emerging pathogens that could present a potential bioterrorism threat as scientifc information about these organisms increases. Children particularly may be vulnerable to a bioterrorist attack, because children have a more rapid respiratory rate, frequent hand-to-mouth behavior, increased skin permeability, higher ratio of skin surface area to mass, and less fuid reserve, compared with adults. Accurate and rapid diagnosis may be more diffcult in children because of their inability to describe symptoms. In addition, adults on whom children depend for their health and safety may become ill or require quarantine during a bioterrorism event. Public health assessment and prioritization of potential biological terrorism agents. Bioterrorism Agents and Categories Category A Category A agents are high-priority agents that include organisms that pose a risk to national security because they: 1. Result in high mortality rates and have the potential for major public health impact; 3. Viral hemorrhagic fever (floviruses [eg, Ebola, Marburg] and arenaviruses [eg, Lassa, Machupo]) Category B Category B agents are second highest priority agents and include agents that: 1. Food safety threats (eg, Salmonella species, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Shigella species) 4. Viral encephalitis (alphavirus [eg, Venezuelan equine encephalitis, eastern equine encephalitis, western equine encephalitis]) 12. Water safety threats (eg, Vibrio cholerae, Cryptosporidium parvum) Category C Category C agents are third highest priority agents, which include emerging pathogens that could be engineered for mass dissemination because of: 1. Category C agents include emerging infectious diseases, such as Nipah virus and hantavirus. Children also may be at risk of unique adverse effects 1 from preventive and therapeutic agents that are recommended for treating exposure to agents of bioterrorism. Further, availability of appropriate pediatric formulations of medical countermeasures may be limited.

When mechanically cleaned diabetes type 1 eye problems buy metformin 850 mg without a prescription, vertical cylinders should be used for instruments with lumens to ensure complete contact of the cleaning solution with the inner surface diabetes mellitus definition medical trusted 850mg metformin. Instruments of unlike metals should not be placed together in the same tray for processing blood sugar yeast infections purchase metformin 850 mg amex, eg signs of diabetes in labs generic metformin 500mg amex, stainless steel instruments should not be placed with aluminum, copper or brass instruments. When cleaning by hand, a solution of warm water and low-foaming detergent should be used. The mixing instructions of the manufacturer of the cleaning agent should be followed. It is recommended that the cleaning solution be changed after each use, eg, set of instruments. It should be confirmed that the lubricant is compatible with the use of sterilization. Lubricants that contain oil bases should not be used; the oil will prevent the sterilizing agent from fully contacting the surface of the instruments. New and repaired instruments should be inspected to assure all moving parts are in good working order including: the box lock, tips align as well as teeth if present; cutting edges of scissors are sharp and free of burs or other damage; screws are in place and not loose or stripped; and ratchets hold the instrument closed without springing open. If defects are found, the instrument(s) should be immediately shipped back to the manufacturer or instrument repair business to be repaired or replaced. Manufacturers may require pretreating in steam sterilization in order to harden the coating on the instruments prior to routine cleaning and sterilization. Loaner instrumentation is defined as instruments or instrument sets borrowed from a 9 vendor for surgical procedures that are returned to the vendor after use. This will allow the facility to identify instrumentation that requires special handling and determine if the facility decontamination equipment and machines will meet the recommendations of the manufacturer. Additionally this avoids delays in processing the instruments and therefore, avoids delaying the scheduled surgical procedure(s). The equipment and instruments, including instrument trays that the instruments arrived in, should be inspected to assure all moving parts are in good working order including the box lock; tips align as well as teeth if present; cutting edges of scissors are sharp and free of burs or other damage; screws are in place and not loose or stripped; and ratchets hold the instrument closed without springing open. Defective instruments and equipment should be immediately documented and reported to the surgery department supervisor in order to avoid delaying the surgical procedures(s). The request for loaner instruments should be made well in advance of when the surgical procedure(s) are scheduled to allow time to inventory, inspect, and reprocess the instruments and/or implants. Scrub sinks and hand washing stations should not be used for cleaning 9 instruments. The document provides requirements and guidelines for decontamination areas/rooms. The following environmental controls should be maintained in the decontamination room: (1) Six-10 air exchanges per hour (2) the room should have a door that is kept closed with the exception of when contaminated instruments are being delivered in order to maintain negative pressure. Low temperature aids in inhibiting the growth of microorganisms (4) Recommended relative humidity varies from organization to 9 organization. The station should be positioned, so it is accessible within 10 9 seconds or 30 meters of potential chemical exposure. It is recommended that disposable hair cover, facemask, gown, gloves and shoe covers be worn. Education and training should be completed for the: (1) decontamination of new instruments, equipment and devices. The following recommendations are general guidelines to follow for testing the 15 functionality of instruments: A. Scissors, excluding microscissors, should be sharp enough to cut two 4 x 4 sponges with little effort. Ratcheted instruments should smoothly close and lock and not spring open when the ring handles are lightly tapped in the palm of the hand. The jaws of hinged instruments should close evenly with no gaps, and the tips evenly lined. The teeth of tissue forceps should fit smoothly in the groove of the opposite side. The ratchets on self-retaining retractors should be tested to ensure they remain in the open position and release with little effort. Instruments that are not in proper working order should be removed and replaced in the instrument set. Studies have confirmed that the use of colored tape does not interfere with the 21 sterilizing agent contacting the underlying surface of the surgical instruments. The following are recommended techniques for the application of tape to surgical 9 instruments: A. Alcohol should be used to wipe the site of the instrument where the tape will be applied in order to remove lubricant or moisture that can prevent the tape from sticking to the instrument. The site for application of the tape should always be the shank of the instrument in order for the tape to lay flat and avoid any gaps. Tape should not be applied to the rings of the instrument since the rounded surface is not conducive to complete adherence of the tape to the instrument surface. The tape should be cut at an angle to allow the edges to lay flat when applied to the shank of the instrument. It is recommended to cut a length of tape that can be wrapped around the shank one-and-one-half times. The tape should be applied with firm but gentle tension without stretching the tape. After the tape has been applied, the instruments should be sterilized to allow the heat to bond the tape to the instruments. If the tape becomes worn, discolored, and/or is peeling from the instrument it should be removed as soon as possible and replaced to avoid the tape from coming loose and entering a surgical wound. The cleaning and decontamination of devices that have been used on high-risk tissue (Table 1) and high-risk patients is controversial. Intended use of medical devices: (1) Critical devices: Those that are used upon sterile tissue. The following are based upon recommendations that apply to the decontamination 2 of instruments contaminated with high-risk tissues from high-risk patients. Devices, such as surgical instruments, that are constructed in such a manner that allows for effective cleaning procedures that result in the complete removal of tissue can be cleaned and prevacuum steam sterilized at 134 C (273 F) for 18 minutes or more or 121 C (250 F) to 132 C (270 F) for one hour in a gravity-displacement sterilizer. For devices that are difficult to clean, it is recommended that they be destroyed. However, even though the destruction of devices is the safest method, it also may not be the most practical or cost effective for a healthcare facility. The devices are then cleaned, assembled, wrapped and sterilized by conventional methods. Flash sterilization should never be used for reprocessing devices contaminated with high-risk tissue. The healthcare facility should have a tracking system in place in order to recall devices that have been used on high-risk patients and high-risk tissue. For example, if the healthcare facility has two ophthalmology instrument trays, they should be numbered eye #1 and eye #2. Instruments targeted for disposal by incineration should be placed in a leak-proof container with tight-fitting lid labeled hazardous and immediately transported to the incinerator. A hazard label should be affixed to each package or instrument tray and stored in specially marked, rigid sealed containers to prevent the re-introduction of the instruments into the routine sterile storage of instruments. |