Archana Dixit MD, MRCOG

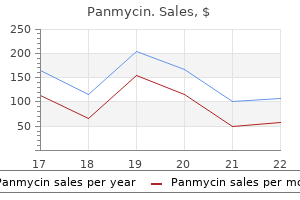

Modern Anatomy and African Anatomy Three areas proved to be problematic in defining or identifying modern anatomy: (1) the anatomy of early modern humans as defined in the literature is not especially similar from place to place; (2) for the most part antimicrobial gloves cheap panmycin online american express, early modern human populations have some of the fea tures that are uniquely common in preceding archaic populations from the same region ure 11 antibiotics for k9 uti buy 500 mg panmycin. Together bacteria zone cheapest generic panmycin uk, this means what paleogenetics has now also shown: anatomical modernity does not have a single unique African source in a new species that replaces all native populations without mixture antimicrobial dressings proven panmycin 250 mg. There is no single source of anatomical modernity and attempts to define a set of modern human features have not failed because of the competence and thoroughness of the investigators, but because there is no such set. Africa has played a unique role in the evolution of recent humanity (Caspari, 2007; Smith et al. However, in contending African origins, neither Protsch nor Brauer insisted that early humans of modern form in Africa implied unique African origins. This clearly shows why assimilation is a multiregional model, as we described above, but we believe this formulation remains problematic, as author after author as also described above fails to arrive at a clear and unique description of modern humans that would reflect a common African influence. Moreover, the earliest modern crania from regions away from Africa have no special similarities that are both common to each other and shared with early modern Africans ure 11. Early modern populations in different parts of the world have African influence through descent; genetic analysis continues to confirm this, and the direction of most Pleistocene gene flow is understood to be from the center to the edges in all multiregional models. But early anatomical and genetic evidence shows modern population variations also reflect local ancestry, and we do not see evidence that their modernity can be ascribed to only one of these sources. One might assume this gracility to be a consequence of genetic influences from Africa, conditions spread by dispersing Africans. But it is not evident that dispersing Africans themselves were especially small or gracile. Gracility does appear early in Africa 90, 000 or more years ago at its Southern tip, but it is not evident that the Klasies folk have any specific ancestry for later dispersing groups. The Herto, Omo-Kibish 2, and Jebel Irhoud specimens are robust, and those fossils thought to represent early modern humans immediately out of Africa, for instance at Skhul in Israel, are not particu larly gracile ure 11. In most regions one source of changes in selection resulting in skeletal gracility came from the consequences of changing technology and organization. These crania, to the far left, have African features that might be expected to disperse if modernity was an African change. They are shown here with the (later dated) earliest complete or almost complete modern crania from (left to right) Europe (Pestera cu Oase 2 from Trinkaus, 2010), eastern Asia (Liujiang), and Australia (Kow Swamp 1 and Keilor). These are the earliest specimens with sufficient facial preservation to reflect facial anatomy without the bias that often comes with reconstruction. The question is whether the anatomical features of either Herto or Jebel Irhoud 1 are compelling sources for the shared modern features in the other specimens. These changes were not the same everywhere, guaranteeing that the details of gracility differed from place to place. Moreover, our discussion of genetic modernity (below) suggests that many new genes shared by humans today evolved more recently than the Late Pleistocene and some of these more recent genes likely contribute to anatomical modernity. In spite of these shared aspects of modernity promoted by natural selection and dispersed throughout the human species, members of human popu lations can often be forensically identified (Sauer, 1992). If we use modern to mean similar to living and recent populations, as suggested above, this also is problematic. This, and similar figures, are meant to illustrate similarities, not to prove their presence, which is a statistical question for the samples. If the ~35 kya dating is correct for Pestera cu Oase 2 (middle, from Trinkaus, 2010), a specimen found on the floor of a cave, it is described as the oldest modern human cranium from Europe. Its unfused sphenooccipital synchrondosis and the position of the third molars within their crypts show a subadult age at death. It died at an only slightly older age than the late (~40 kya) Neandertal from Le Moustier, the reconstruction shown below from Thompson and Illerhaus (1998). We believe this is an appropriate comparison because the two lived close together in time and there is similarity in dental development and eruption. There are also anatomical similarities that include the cranial shape, cranial details such as occipital bunning, relative size of the mastoid and paramastoid processes, and weak development of the supraorbital tori. The Pestera cu Oase 2 anatomy is exceptionally similar to some recent Central Europeans. It is compared here with the Medieval Hungarian Avar adult cranium 552 from Mosonszentjanos (above). All three crania are shown at the same approximate size, in the Frankfurt Horizontal (for Le Moustier the position of the bottom of the orbit is uncertain, and its orientation is matched to the other two by cranial contour). These three crania show general similarities that cannot easily be explained by an overwhelming African influence bringing modernity to the two post-Neandertals. The specimens are scaled to the same size (in actuality the cranial lengths are 203 mm [Australian], 212. In all of these crania the greatest breadth is at its base, across the supramastoid crests. The Omo remains are fragmentary and lack faces (there is a facial reconstruction for Omo 1 but we lack confidence in its accuracy). For instance, the interorbital distance is exceptionally great, and above it the supraorbital torus is thick and continuous across the forehead, projecting strongly from the frontal squama so that there is a deep, strongly expressed supraorbital sulcus. In their principal components analysis of Homo erectus, Neandertals, and modern humans rep resented in the Howells data set (1989), White and colleagues show a plot of the first two principal component scores places Omo 2 in the Neandertal distribution and Herto between the Neandertal and modern human distributions (p. In an adjacent plot of the first three principal components of the complete Howells data set the Herto adult also lies outside the human range. We wonder whether even more recent examples of early modern human remains of African descent are modern, in the sense of being like recent and living populations. For instance, considering Skhul, while there has been much discussion about the affinities of the Skhul males, the less well-preserved females have generally not been the focus of these con siderations. McCown and Keith (1939) identify this specimen as a 30 to 40-year-old woman, including incomplete cranial and mandibular remains and portions of the forearm long bones. She presents a mixture of features, as all of the Skhul specimens do, but we contend that some of these are unmatched in any recent or living woman from anywhere ure 11. The point is that the early modern Africans of the late Middle Pleistocene and early Upper Pleistocene cannot actually be described as modern, and certainly not as gracile. There is little reason to look to this sample for the origin of modern features, especially gracile modern features, seen around the world. This is not to deny that Africa was a significant source of new genetic variation during human evolution. To the contrary, for most of the Pleistocene the predominant direction of gene flow was from the more densely occupied African center to the more sparsely occupied peripheries of the human range (Templeton, 2007; Wolpoff et al. The dominance of African population size for most of the Pleistocene has widely discussed consequences (Eller et al. The earliest of the early modern Africans are not modern in our sense and had many descendents, including some Neandertals (Wolpoff and Lee, 2007, 2012). The Biological Origin of All Modern Populations Involves Mixture If it is true that modern populations are not the unique descendents of a recent group of Africans, it is also the case that Neandertals and other archaic populations did not evolve into later Europeans in isolation from the rest of the world and in parallel to it; that would be a polygenic explanation (Wolpoff and Caspari, 1997a). In Europe, where the case against mixture always seemed strongest, there was persistent contrarian evi dence, especially from Central European sites, that the earliest modern (post-Neander tal) crania retained a significant number of regionally predominant features that were common in Neandertals and rare in other populations (Frayer, 1992, 1993; Frayer et al. The earliest modern (post-Neandertal) crania 30, 000 years in age and older include: ~35 kya Pestera cu Oase seen in Figures 11. There is no single set of Neandertal features in all these crania; different specimens have different features that were common in Neandertals, precisely the pattern found in paleogenetics where most non-Africans have some Neandertal genes that, by and large, appear in dif ferent combination from person to person.

Long-established drivers of land degradation continue to increase across much of the world infection from tattoo discount panmycin 250mg line, including agricultural activities {3 bible black infection order panmycin mastercard. More recent global change drivers antimicrobial wound spray purchase panmycin 500mg otc, such as climate change and atmospheric nitrogen deposition antibiotic meaning discount panmycin 250 mg free shipping, further exacerbate impacts {3. We are now in a qualitatively different and novel world, compared to only a few decades ago, and the combination of drivers creates significant challenges to restore degraded land and mitigate further degradation (established but incomplete). Few, if any, areas of the world are now free of some form of human influence (well established) and some systems are experiencing unprecedented challenges. This high dependency on imported commodities means that a large share of the environmental impacts of consumption is felt in other parts of the world. The physical quantity of goods traded internationally only represents one third of the actual natural resources that were used to produce these traded goods. The sustainability of the commodity production systems that support global supply chains is thus substantially shaped by the sourcing and investment decisions of market actors who may have little direct connection to the production landscapes (established but incomplete). Moreover, the globalized nature of many commodity supply chains potentially elevates the relative importance of global scale factors such as trade agreements, market prices and exchange rates, as well as distant linkages related to buyer and investment preferences, over national and regional governance arrangements and the agency of individual producers (inconclusive). Addressing this complexity to avoid and reverse land degradation therefore requires the building of effective multi-sector and multi-stakeholder partnerships that span national boundaries (established but incomplete) {3. Economic growth and per capita consumption, more than poverty, is one of the biggest threats to sustainable land management globally (established but incomplete) {3. Extreme poverty, combined with resource scarcity, can contribute to land degradation and unsustainable levels of natural resource use, but is rarely the major underlying cause (well established). Many of the most marked changes in how land is used and managed come from individual and societal responses to economic opportunities, such as a shift in demand for a particular commodity or improved market access, moderated by institutional and political factors (established but incomplete). For example, clearance of native vegetation and land degradation across much of Latin America and Asia is linked to agricultural expansion and intensification at a commercial scale for export markets (well established). Reducing poverty, although a priority for sustainable development, is insufficient to mitigate land degradation if not accompanied by additional measures. Efforts to reverse degradation therefore require a combination of local and regional poverty alleviation strategies, including the adoption of pro-poor food production systems, together with efforts to improve the enforcement of public regulations for sustainable land uses, and strengthening the accountability of global market actors in effectively supporting such strategies. The highly interconnected and globalized nature of indirect drivers of land degradation and restoration means that the outcome of any global, regional or local intervention can be highly unpredictable, yet contextual generalizations are possible (established but incomplete) {3. For example, changes in currency exchange rates, and cascading effects on the profitability of a given commodity, can markedly accelerate or decelerate the clearance of native vegetation for agriculture within a single year {3. However, with an improved understanding of the interactive effects amongst different drivers, it is possible to make predictions that are valid under a certain range of conditions. For example, agricultural intensification and agroforestry practices can help reduce the pressure on remaining areas of native vegetation under certain conditions (such as inelastic demand for staple crops), but unless such measures are coupled with increased enforcement of land-use policies they can result in a rebound effect that increases pressure on natural resources (established but incomplete) {3. Land degradation in any given place is rarely the consequence of a single anthropogenic driver, but is instead the result of a diverse and frequently mutually-reinforcing set of human activities and underlying drivers (well established) {3. Typically, at least three types of indirect driver, such as economic, technological and institutional, underpin any direct driver of land degradation or restoration (established but incomplete). The complexity of drivers that commonly underpin land degradation highlights the fact that single factors, such as high rural population density, rarely provide an adequate underlying explanation on their own for observed impacts (established but incomplete) {3. Land degradation is typically the result of multiple direct drivers, especially in instances of severe degradation. This combination of drivers has resulted in large expanses of economically important grazing lands, including in North America, being transformed to fire-prone annual grass monocultures (well established) {3. The multi-causality of land degradation requires commensurately holistic policy responses that operate across multiple scales and combine both regulatory and incentive based measures (established but incomplete). Rapid expansion and inappropriate management of agricultural lands (including both grazing lands and croplands), especially in dryland ecosystems, is the most extensive land degradation driver globally (well established) {3. The expansion of grazing lands has largely stagnated globally with evidence for an approximate 1% decline in grazing land area over the past decade. Grazing pressure has been stable or only moderately increasing across the major land areas globally, although there are regional exceptions such as Southern Asia. Over half of grazing lands occur in dryland environments that are highly susceptible to land degradation (established but incomplete) {3. More recently intensification and increasing industrialization of livestock production systems, especially in developed countries, has resulted in an increasing reliance on mixed crop-livestock production systems and industrialized "landless" systems. Marked drops in nitrogen-use efficiency (change in yield per unit of fertilizer input) in many parts of the world, particularly the Asia Pacific region, often accompanied by continued excessive fertilizer application, underscore the critical importance of sustainable agricultural practices, including conservation agricultural techniques, to maintain yield improvements (established but incomplete) {3. Increases in consumption levels of many natural resources underpin increasing levels of degradation in many parts of the world (well established), with slow rates of adoption of sustainable production systems (established but incomplete) {3. Projections to 2050 suggest that one billion ha of natural ecosystems could be converted to agriculture by that time. More than half of agricultural expansion in the last three decades has occurred in relatively intact tropical forests. Traditional fuelwood and charcoal continue to represent a dominant share of total wood consumption in low income countries, up to 70%, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa (well established). Under current projections efforts to intensify wood production in plantation forests, together with increases in fuel-use efficiency and electrification are only likely to partly offset the pressure on native forests (unresolved). Adoption of more sustainable production systems continues to be slow, as seen, for example, by a slowdown in the expansion of the area of certified forests. More than half of the terrestrial surface of the Earth has fire regimes outside the range of natural variability, with changes in fire frequency and intensity posing major challenges for land restoration (established but incomplete) {3. Some changes in fire regimes, particularly in tropical forests, are sufficiently severe that recovery to pre-disturbance conditions may no longer be possible. Increases in international trade, intensification of land use and urbanization have meant that few areas of the planet are free of invasive species (established but incomplete) {3. Once established, the eradication of many invasive species is often very expensive, if not impossible, underscoring the need to develop proactive strategies to pre-empt invasions, including through inspections, research and education. Activities related to industrialization, infrastructure development, urbanization, and many extractive industries result in complete transformation of ecosystems, accompanied by near or complete loss of biodiversity and ecosystem function and the services those ecosystems provide (well established) {3. Infrastructure, industrial development and urbanization activities, often replace natural ecosystems with impervious or contaminated surfaces such as asphalt, concrete and rooftops, leading to the one of the most severe forms of land degradation in the form of soil sealing. If population densities in cities remain stable, the extent of built-up areas in developed countries is expected to increase by 30% and triple in developing countries between 2000 and 2050. Under more extreme scenarios of increasing population density and economic development, the extent of built-up areas globally may increase to over 2% of the global land area over this same time period. New urban design and green technologies that incorporate features that promote sustainability and delivery of ecosystem services can play an important role in restoring some of the ecosystem functions and services of built environments. The importance of climate change for land degradation is most prominent through its role in exacerbating the impacts of other human activities (established but incomplete) {3. Heavy rainfall events and storms as well as heat waves and droughts are predicted to increase in frequency over several parts of the globe, with cascading effects on the frequency, intensity, extent and timing of other drivers such as fires, pest and pathogen outbreaks, species invasions, soil erosion and landslides (established but incomplete). In the last decade hundreds of companies have made pledges to reduce their impacts on forests and on the rights of local communities, with many committing to eliminate deforestation from their supply chains entirely by 2020. In the same period, many governments and civil society groups have made ambitious commitments to restore hundreds of millions of hectares of degraded land. New players, such as the finance sector, who until recently have been completely detached from the mainstream sustainability agenda are also starting to make explicit commitments to avoiding environmental harm. This assessment is concerned with changes in both the extent of human activities and behaviours that drive land degradation, as well as the type or intensity of those activities. Specifically, we describe the different drivers of land degradation and the extent and severity of these drivers across biomes, as well as how these drivers link to declines in biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services (described fully in Chapters 4 and 5). Exploration of the interactions among drivers that further exacerbate the functioning of ecosystems, including the role of climate change as a threat multiplier of degradation drivers, are a key focus in this chapter. A thorough examination of land degradation drivers provides a critical first step toward an improved understanding of how we may successfully restore degraded lands and avoid further degradation in the future (see Chapters 6 and 8). Discount panmycin line. Thermoplastic biocomposits based on hybrid yarns - Sarah Vogt.

People experiencing sleep state misperception often sleep for normal durations virus joke cheap panmycin online, yet severely overestimate the time taken to fall asleep do they give antibiotics for sinus infection panmycin 500 mg generic. They may believe they slept for only four hours while they antimicrobial grout discount panmycin 500mg on-line, in fact virus killer buy panmycin 500mg with amex, slept a full eight hours. Exercise-induced insomnia is common in athletes in the form of prolonged sleep onset latency. Sleep studies using polysomnography have suggested that people who have sleep disruption have elevated nighttime levels of circulating cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone They also have an elevated metabolic rate, which does not occur in people who do not have insomnia but whose sleep is intentionally disrupted during a sleep study. The question remains whether these changes are the causes or consequences of long-term insomnia. Frequent moving between sleep stages occurs, with awakenings due to headaches, the need to urinate, dehydration, and excessive sweating. When the person stops drinking, the body tries to make up for lost time by producing more glutamine than it needs. The increase in glutamine levels stimulates the brain while the drinker is trying to sleep, keeping him/her from reaching the deepest levels of sleep. Insomnia: Classification, Types and Patterns 121 Benzodiazepine-induced Like alcohol, benzodiazepines, such as alprazolam, clonazepam, lorazepam and diazepam, are commonly used to treat insomnia in the short-term (both prescribed and self medicated), but worsen sleep in the long-term. Opioid-induced Opioid medications such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, and morphine are used for insomnia that is related to pain due to their analgesic properties and hypnotic effects. By producing analgesia and sedation, opioids may be appropriate in carefully selected patients with pain-associated insomnia. Risk factors Insomnia affects people of all age groups but people in the following groups have a higher chance of acquiring insomnia. Further studies have revealed that those with lower levels of cortisol upon awakening also have poorer memory consolidation in comparison to those with normal levels of cortisol. Studies support that larger amounts ofcortisol released in the evening occurs in primary insomnia. In this case, drugs related to calming mood disorders or anxiety, such as antidepressants, would regulate the cortisol levels and help prevent insomnia. Estrogen A number of postmenopausal women have reported changes in sleep patterns since entering menopause that reflect symptoms of insomnia. Lower estrogen levels can cause hot flashes, change in stress reactions, or overall change in the sleep cycle, which all could contribute to insomnia. Progesterone Low levels of progesterone throughout the female menstruation cycle, but primarily near the end of the luteal phase, have also been known to correlate with insomnia as well as aggressive behavior, irritability, and depressed mood in women. Around 67% of women have problems with insomnia right before or during their menstrual cycle. Lower levels of progesterone can, like estrogen, correlate with insomnia in menopausal women. A common misperception is that the amount of sleep required decreases as a person ages. The ability to sleep for long periods, rather than the need for sleep, appears to be lost as people get older. Some elderly insomniacs toss and turn in bed and occasionally fall off the bed at night, diminishing the amount of sleep they receive. A qualified sleep specialist should be consulted in the diagnosis of any sleep disorder so the appropriate measures can be taken. Past medical history and a physical examination need to be done to eliminate other conditions that could be the cause of the insomnia. After all other conditions are ruled out a comprehensive sleep history should be taken. The sleep history should include sleep habits, medications (prescription and non-prescription), alcohol consumption, nicotine and caffeine intake, co-morbid illnesses, and sleep environment. The diary should include time to bed, total sleep time, time to sleep onset, number of awakenings, use of medications, time of awakening and subjective feelings in the morning. The sleep diary can be replaced or validated by the use of out patientactigraphy for a week or more, using a non-invasive device that measures movement. Workers who complain of insomnia should not routinely have polysomnography to screen for sleep disorders. This test may be indicated for patients with symptoms in addition to insomnia, including sleep apnea, obesity, a risky neck diameter, or risky fullness of the flesh in the oropharynx. Usually, the test is not needed to make a diagnosis, and insomnia especially for working people can often be treated by changing a job schedule to make time for sufficient sleep and by improving sleep hygiene. The sleep study will involve the assessment tools of a polysomnogram and the multiple sleep latency test and will be conducted in a sleep center or a designated hotel. Specialists in sleep medicine are qualified to diagnose the many different sleep disorders. Patients with various disorders, including delayed 124 the Effortless Sleep Method: Cure for Insomnia. When a person has trouble getting to sleep, but has a normal sleep pattern once asleep, a delayed circadian rhythm is the likely cause. In many cases, insomnia is co-morbid with another disease, side-effects from medications, or a psychological problem. Prevention Going to sleep and waking up at the same time every day can create a steady pattern which may help to prevent or treat insomnia. Avoidance of vigorous exercise and anycaffeinated drinks a few hours before going to sleep is recommended, while exercise earlier in the day is beneficial. The bedroom should be cool and dark, and the bed should only be used for sleep and sex. The beneficial effects, in contrast to those produced by medications, may last well beyond the stopping of therapy. Medications have been used mainly to reduce symptoms in insomnia of short duration; their role in the management of chronic insomnia remains unclear. Several different types of medications are also effective Insomnia: Classification, Types and Patterns 125 for treating insomnia. However, many doctors do not recommend relying on prescription sleeping pills for long-term use. It is also important to identify and treat other medical conditions that may be contributing to insomnia, such as depression, breathing problems, and chronic pain. Non-pharmacological Non-pharmacological strategies have comparable efficacy to hypnotic medication for insomnia and they may have longer lasting effects. Hypnotic medication is only recommended for short-term use because dependence with rebound withdrawal effects upon discontinuation or tolerance can develop. Non pharmacological strategies provide long lasting improvements to insomnia and are recommended as a first line and long term strategy of management. The strategies include attention to sleep hygiene, stimulus control, behavioral interventions, sleep-restriction therapy, paradoxical intention, patient education and relaxation therapy. Some examples are keeping a journal, restricting the time spent awake in bed, practicing relaxation techniques, and maintaining a regular sleep schedule and a wake-up time. Behavioral therapy can assist a patient in developing new sleep behaviors to improve sleep quality and consolidation. Behavioral therapy may include, learning healthy sleep habits to promote sleep relaxation, undergoing light therapy to help with worry-reduction strategies and regulating the circadian clock. Stimulus control therapy is a treatment for patients who have conditioned themselves to associate the bed, or sleep in general, with a negative response.

Semal and Coll (2009) have argued that in this part of Europe there is no convincing evidence of a Mousterian as young as the direct dates obtained on the Spy Neandertal remains antibiotic news order panmycin american express. To date only two deciduous teeth (a left dm1 antibiotics diabetes buy cheap panmycin 500 mg line, Cavallo B antimicrobial vs antibiotics order panmycin 500 mg without a prescription, and a right dm2 antimicrobial wood order 250 mg panmycin with visa, Cavallo C) from the Grotta del Cavallo (Italy) have been described in Uluzzian context. On metrical and morphological grounds, in particular due to some level of taurodontism, both teeth were later attributed to Neandertals (Churchill and Smith, 2000; Palma di Cesnola and Messeri, 1967). These classifications were probably influenced in part by the notion that the Uluzzian, like the Chatelperronian, could be the result of the evolution of the local Mousterian. At the Grotta del Cavallo, possible admixture of Uluzzian and Aurignacian assemblages in the uppermost Uluzzian levels of layer D has been claimed by Gioia (1990). However, even if demonstrated, this mixing is unlikely to have affected the lower Uluzzian archeological layers, where Cavallo B was discovered. Layer admixture is unlikely, as the abundant lithic assemblage of this layer is technologically homogeneous and clearly distinct from that of the overlying Aurignacian (Tsanova and Bordes, 2003). One can rather suspect issues with the pretreatment of the 14C samples, which is crucial for this time period and was much improved in the last decade (Higham, 2010). Like the Bohunician from the Czech Republic (Svoboda and Bar-Yosef, 2003), the Bachokirian is characterized by the use of Levallois 6 the Makers of the Early Upper Paleolithic 231 technology to produce elongated blanks. At Bacho Kiro these blades have been retouched in particular to produce endscrapers. It is therefore of the utmost importance to identify the makers of assemblages such as the Bohunician or the Bachokirian in Central Europe. In their original description, Glen and Kaczanowski (1982) suggested that the specimen could be closer to the Neandertal morphology, mostly because of its large bucco-lingual diameter. Unfortunately, the original material from Bacho Kiro layer 11 has been lost, and it is therefore impossible to assess truly discriminant features on the dm1 such as enamel thickness or cervical outline. The archeological record of the Jankovichian is quite problematic (Svoboda and Siman, 1989), and in the case of the Remete cave, it seems most likely that the assemblage represents a late Micoquian with some foliate elements (Allsworth-Jones, 1990; Gabori-Csank, 1983). Proto-Aurignacian Human remains found in proto-Aurignacian contexts are extremely scarce. In the site of Le Piage (France), skeletal fragments of a fetus (or newborn) have been discovered in a proto Aurignacian layer but have remained unidentifiable (Beckouche and Poplin, 1981). Since then, dental material has been yielded by the site but is still unpublished. The crown is of rather small dimension and its morphology is said to be modern (Formicola, 1989). The tooth from Riparo Bombrini, therefore, probably dates to this interval of time, but a more refined chronological attribution could only be obtained through dating the stratigraphic sequence of the site where it was recovered. Unfortunately, the human cranial fragments allegedly yielded by the different layers of the site can be refitted, and the ubiquitous presence of cutmarks on all these remains origi nally assigned to layers ranging from the Aurignacian to the Azilian suggest that in fact all the remains may be derived from one layer only, likely the Magdalenian level of the site, by far the richest in human remains (Gambier, 1990). Obermaier in the El Castillo cave before the First World War is assigned to layer 18, as defined by the new excavation by V. Layers 18b and 18c of new excavations yielded some lithics that fit better with the proto-Aurignacian than Early Aurignacian, but also lithics that would fit well into underlying Mousterian layers. Therefore, the hypothesis of an admixture of industries could be considered as an alternative explanation for the mixed techno-typological pattern of the layer. Three individuals may have been repre sented by cranial fragments, a second right lower molar and a fragmentary child mandible bearing a dm1 and dm2 on the right side as well as an unerupted right M1. An unpublished description by Vallois has been made available and was commented on by Garralda et al. Additional discoveries out of any archaeological context, but nevertheless contemporaneous with an early phase of the Aurignacian in their geographical domain, should be added to this list. Among them one should mention a fragment of right parietal, a lower right permanent central incisor, a lower right lateral incisor, a right premolar, an upper right permanent canine, a deciduous lower central incisor, and a fragment of an immature right mandible bearing the second deciduous molar and the first permanent molar (specimen #599) (Glen and Kaczanowski, 1982). Churchill and Smith (2000) generally concluded that these Bacho Kiro specimens are ambiguous but closer to modern humans. The specimen was initially described by Hillebrand (1914) as Neandertal; how ever, this tooth, which displays four cusps and lacks a midtrigonid crest, is actually quite modern in its morphology. The positive association of this material with the Early Aurignacian is unclear, as the sedimentation processes in the site were rather chaotic and the layers are affected by cryoturbation and mechanical distur bances (Kaminska et al. As the layer also contains foliate elements, the tooth was also sometimes assigned to Szeletian (Churchill and Smith, 2000; Hillebrand, 1914). Further west, at Fossellone, one of the caves of the Monte Circeo (Italy), a maxillary fragment (Fosselone 1), could be associated with a rather early Aurignacian (Mallegni and Segre-Naldini, 1992). A scapula fragment (Fosselone 2) of modern morphology is also reported from the site, but its chronostratigraphic context is uncertain. At Fontana Nuova di Ragusa, 6 the Makers of the Early Upper Paleolithic 233 Figure 6. However, the extraordinary conditions of their discovery (the bones were recovered by L. Bernabo Brea in the spoil heap of the original unsystematic excavations) and the sugges tion that the lithic assemblage is typologically assignable to the Late Epigravettian industry (Martini et al. Human remains yielded by some French sites are assigned to Early Aurignacian assem blages. In Fontechevade, one fragmentary child mandible, an upper first molar and a fragmentary adult parietal may also come from a rather ancient part of the Aurignacian layers (Garralda, 2006; Chase and Teihol, 2009). One of the most securely dated sets of specimens comes from the site of Brassempouy (Henry-Gambier et al. This site has yielded a dental series, a fragment of mandible, a cranial fragment, and two distal hand phalanges in a well-recorded stratigraphical context. As is generally the case, the metrical analysis of the isolated teeth did not allow for a clear taxonomical assignment (Henry-Gambier et al. Four individuals display a 90% and one a 63% posterior probability of being modern (Bailey et al. Even more complete remains come from the site of La Quina-Aval (France) where Early Aurignacian layers dated at 32. Among the preserved material, two immature mandibles and a lower premolar have been identified. The mandible Quina-Aval 4 displays a dental arc that is anteriorly narrow and possesses a clear bony chin ure 6. The associated dental material does not display any Neandertal features and there is little doubt about the modern nature of this collection, which to date likely represents the best evidence in Western Europe of the modern nature of the Early Aurignacian assemblage makers (Verna et al. Direct dating of the remains gave inconsistent results due to contamination by consolidant (Sinitsyn, 2004). Up until now, only preliminary descriptions of the remains have been published (Debets, 1955; Gerasimova, 1987). Debets (1955) emphasized the lack of Neandertal-like features and similarities in the facial propor tions with the Grimaldi material. At Pestera cu Oase (Romania) human remains were discovered in the depths of a karst outside of any archaeological context (Rougier et al. |