Allen Ray Sing Chen, M.D., M.H.S., Ph.D.

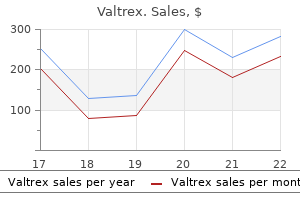

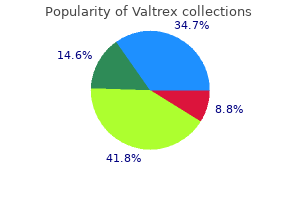

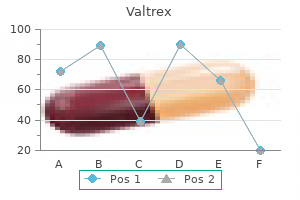

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/profiles/results/directory/profile/0008071/allen-chen My loyal assistant for the last 10 years antiviral brand names buy valtrex 1000mg low price, Tejal patel hiv infection rate in argentina discount valtrex 500 mg line, has provided amounts of all-round care to cover for my time hiv infection transmission cheap valtrex 500 mg otc. I wish to thank my professor friends who spared their valuable time in reviewing the chapters hiv infection ukraine purchase valtrex without prescription. I hope that my quest to document signifcant and up-to-date information has been successful. I invite readers and educators to send their suggestions so that I can include them in the next edition. The structure, content, and production values of this book will be shaped by its relationship with educators and readers. I would like to recognize and thank the members of the book team, who indeed worked hard, to bring this book to you. Shri Jitendar p Vij (chairman and Managing Director), Jaypee Brothers Medical publishers, illuminated the path for this book with his creative ideas and dedication. The insights and skills of Dr Richa Saxena (Editor-in-chief) helped in polishing this book to best meet the needs of students and faculty alike. Mr Ankit Vij (Managing Director), the young and dynamic leader, took personal interest and laid out each page of the book to achieve the best possible placement of text, fgures, and other elements. The suggestions from Mr Saket Budhiraja (Director-Sales and Marketing) were very practical and meaningful. Mr Tarun Duneja (Directorpublishing) demonstrated his untiring expertise during each step of the production process. I would like to thank Ms Sunita Katla (publishing Manager) for her eforts towards the fnalisation of the book. Dr Rimpal chauhan, chandani, priti, falguni, Rina, Rashmi, Tejal, Bimal and Hansika, my students, have collaborated on the illustrations for this book. So I am thankful to prof Ravi Tiwari, prof Girish Mishra, prof Yojana Sharma, Dr Hiren Soni, Dr Siddharth Shah, Dr Nimesh patel and pG students for their valuable and meaningful discussions. I wish to especially thank several of my academic colleagues for their helpful contribution to this book. Majority of them generously provided their time and expertise and reviewed the chapters. Anatomy and Physiology of Nose and Paranasal Sinuses 29 Anatomy of Nose 30 External Nose 30; Internal Nose 30; Anatomy of Paranasal Sinuses 37 physiology of Nose 39 Respiration 39; Air-Conditioning of Inspired Air 40; Protection of Airway 40; Vocal Resonance 41; Nasal Refexes 41; Olfaction 41 physiology of paranasal Sinuses 41 Functions 41; Ventilation of Sinuses 42 3. Anatomy and Physiology of Larynx and Tracheobronchial Tree 61 Anatomy of Larynx 61 Cartilages 61; Joints 62; Membranes and Ligaments 62; Cavity of the Larynx 63; Mucous Membrane of the Larynx 64; Lymphatic Drainage 64; Spaces of the Larynx 64; Functional Divisions of Vocal Folds 65; Phase xii Diference 65; Muscles of Larynx 65; Nerve Supply of Larynx 66; Development 67 functions of Larynx 68 Protection of Lower Airways 68; Phonation and Speech 68; Respiration 68; Fixation of Chest 68 Anatomy of Tracheobronchial Tree 68 Trachea and Bronchi 68; Tracheal Cartilages 68; Mucosa 69; Bronchopulmonary Segments 69 5. Anatomy of Neck 72 Surface Anatomy 72; Triangles of Neck 73; Cervical Fascia 74; Lymph Nodes of Head and Neck 75; Neck Dissection 78; Thyroid Gland 78; Parathyroid Glands 79; Development 79 6. Bacteria and Antibiotics 80 Bacteria 81 Staphylococci 81; Streptococci 83; Corynebacterium Diphtheriae 83; Neisseria Species 84; Morexella Catarrhalis 84; Haemophilus Infuenzae 84; Bordetella Pertussis 84; Pseudomonas Aeruginosa 84; Enterobacteriaceae 84; Anaerobes 84; Microaerophilic Bacteria 84; Mycobacteria 84; Mycoplasma Pneumoniae 85; Chlamydiae 85; Spirochaetes 85 Antibiotics 85 Inhibitors of Bacterial Cell Wall Synthesis (Beta-Lactam Antibiotics) 86; Inhibitors of Nucleic Acid Synthesis 88; Inhibitors of Bacterial Protein Synthesis (Ribosomal) 88; Antitubercular Drugs 89; Nonspecifc Antiseptics 90 7. Fungi and Viruses 92 fungi 93 Antifungal Therapy 93 Viruses 94 Antivirals 95 Pandemic Infuenza A H1N1 (Swine Flu) 96 8. History and examination 107 Otorhinolaryngology 107; History Taking 108; Physical Examination 108; General Set-Up 109; Swellings and Ulcers 109; Examination of Cranial Nerves 115; Headache 115; Facial Pain 120; Temporomandibular (Craniomandibular) Disorders 121 Section 2: ear 10. Otologic Symptoms and examination 125 Ear Symptoms 125 Ear Examination 125 otalgia (Earache) 128 otorrhea 130 Assessment 131 Ear polyp 132 Tinnitus 132 Hyperacusis 135 11. Conductive Hearing Loss and Otosclerosis 149 Classifcation of Hearing Loss 149; Conductive Hearing Loss 149; Otosclerosis 150; Stapedectomy 153 13. Sensorineural Hearing Loss 156 Sensorineural Hearing Loss 157; Labyrinthitis 158; Syphilis 158; Cisplatin 160; Aminoglycoside Antibiotics 160; Noise Trauma 160; Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss 161; Presbycusis 162; Genetic Sensorineural Hearing Loss 163; Non-Organic Hearing Loss 163; Degree of Hearing Loss 164; the Only Hearing Ear 165 14. Hearing Aids and Cochlear implants 173 Training 173; Hearing Aids 174; Assistive Devices 177; Implantable Hearing Aids 177; Cochlear Implants 178; Auditory Brainstem Implant 182 16. Diseases of external ear and Tympanic Membrane 183 Disorders of Auricle 183 Congenital Disorders 183; Traumatic Disorders 185; Erysipelas 186; Perichondritis and Chondritis 186; Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Chronica Helicis 186; Relapsing Polychondritis 186 Disorders of External Auditory canal 187 Congenital Disorders of External Auditory Canal 187; Trauma of External Auditory Canal 187; Foreign Bodies of Ear 187; Ear Maggots 187; Otitis Externa 187; Otomycosis 189; Furunculosis 189; Keratosis Obturans 189; Ear Wax 190; Ear Syringing 190; Herpes Zoster Oticus-Ramsay Hunt Syndrome (Varicellazoster Virus) 191; Bullous Otitis Externa and Myringitis 191 Disorders of Tympanic Membrane 191 Granular Myringitis 191; Malignant or Necrotizing Otitis Externa 191; Retracted Tympanic Membrane 191; Tympanosclerosis 192; Perforation of Tympanic Membrane 192; Traumatic Rupture of Tympanic Membrane 192 17. Disorders of eustachian Tube 194 Anatomy 194; Physiology 196; Examination of Eustachian Tube 196; Tests for Eustachian Tube Function 197; Obstruction of Eustachian Tube 198; Patulous Eustachian Tube 199 18. Acute Otitis Media and Otitis Media with effusion 200 Acute otitis Media 201 Etiopathology 201; Clinical Features 201; Diagnosis 202; Treatment 202; Recurrent Acute Otitis Media 203; Acute Necrotising Otitis Media 204 otitis Media with Efusion 204 Etiology 204; Clinical Features 204; Diagnosis 204; Treatment 205; Sequelae and Complications 205; Aero Otitis Media (Otitic Barotrauma) 205 19. Complications of Suppurative Otitis Media 216 Factors Infuencing Development of Complications 217; Pathways of Spread 217; Acute Mastoiditis 218; Masked (Latent) Mastoiditis 219; Extratemporal Complications (Abscesses) 219; Petrositis or Petrous Apicitis 220; Facial Nerve Paralysis 221; Labyrinthitis 221; Extradural (Epidural) Abscess 221; Subdural Abscess or Empyema 221; Meningitis 222; Otogenic Brain Abscess 223; Lateral Sinus Thrombophlebitis 224; Otitic Hydrocephalus 225 21. Tumors of the ear and Cerebellopontine Angle 268 Benign Tumors of External Ear 268; Malignant Tumors of External Ear 269; Tumors of Middle Ear and Mastoid 270; Internal Auditory Canal and Cerebellopontine Angle 273 Section 3: Nose and Paranasal Sinuses 26. Nasal Symptoms and examination 279 History Taking 279 Examination 280 External Nose 280; Vestibule 280; Anterior Rhinoscopy (Examination of Nasal Cavity) 281; Posterior Rhinoscopy 284; Patency of Nasal Cavities 284; Sense of Smell 284; Paranasal Sinuses 284 Special Investigations of Nasal complaints 285 Smell 285; Measurement of Mucociliary Flow 286; Nasal Obstruction 286; Nasal Valves Disorders 287; Radiological Imaging 288; Diagnostic Antrum Puncture 288; Allergic Tests 288 27. Diseases of external Nose and epistaxis 289 Diseases of External Nose 289 Infections 289; Deformities of External Nose 290; Tumors of External Nose 291 Epistaxis 293 Pertinent Anatomy 293; Causes 293; Evaluation 293; Sites of Epistaxis 294; Investigations 294; Treatment 294 28. Allergic and Nonallergic Rhinitis 320 Allergy and Immunology 321 Types of Immunologic (Hypersensitivity) Mechanism 322 Allergic Rhinitis 323 Etiology 323; Classifcation 324; Investigations 326; Treatment 327 Nonallergic Rhinitis (Vasomotor Rhinitis) 330 Pathophysiology 330; Classifcation 330; Clinical Features 331; Investigations 332; Treatment 332 31. Nasal Septum 333 Fracture of Nasal Septum 333; Deviated Nasal Septum 334; Septal Hematoma 336; Septal Abscess 336; Perforation of Nasal Septum 336; Hypertrophied Turbinates 337; Nasal Synechia 337; Choanal Atresia 337 32. Tumors of Nose, Paranasal Sinuses and Jaws 351 Tumors of Nose and paranasal Sinuses 352 Neoplasms in Children 352; Diagnosis 352; Angiofbroma 353; Intranasal Meningoencephalocele 353; Gliomas 353; Nasal Dermoid 353; Monostotic Fibrous Dysplasia 353; Squamous Papilloma 353; Osteomas 353; Pleomorphic Adenoma 353; Chondroma 353; Schwannoma and Neurofbroma 353; Ossifying Fibroma and Cementoma 354; xv Odontogenic Tumors 354; Inverted Papilloma 354; Meningiomas 354; Hemangiomas 354; Hemangiopericytoma 354; Plasmacytoma 354; Malignant Neoplasms 354; Malignancy of Maxillary Sinus 358; Malignancy of Ethmoid Sinus 358; Malignancy of Frontal Sinus 359; Malignancy of Sphenoid Sinus 359; Adenocarcinoma 359; Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma 359; Malignant Melanoma 359; Olfactory Neuroblastoma 359; Sarcomas 359; Rhabdomyosarcoma 360 Tumors and Related Jaw Lesions 360 Management of Jaw Swellings 360; Fissural Cysts 361; Periapical Cysts 361; Follicular (Dentigerous) Cysts 361; Odontogenic Keratocyst 361; Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome 362; Retention Cyst 362; Ameloblastoma 362; Ossifying Fibroma 362; Fibrous Dysplasia 362; Cherubism 362; Adenomatoid Odontogenic Tumor 363 Section 4: Oral Cavity and Salivary Glands 34. Oral Symptoms and examination 365 Oral Cavity 365; Evaluation of Cancer Lesions 369; Salivary Glands 369; Diagnostic Imaging 370; Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology 372 35. Pharyngeal Symptoms and examination 415 Evaluation of pharynx 415 Nasopharynx 415; Oropharynx 416; Laryngopharynx 417 Evaluation of Esophagus 417 Barium Esophagography 418; Esophageal Manometry 420; Ambulatory 24-Hours Esophageal pH Recording 420; Esophagoscopy 420 Dysphagia 420 Evaluation 421 39. Pharyngitis and Adenotonsillar Disease 423 Pharyngitis 423; Infectious Mononucleosis 424; Streptococcal Tonsillitis-Pharyngitis 424; Faucial Diphtheria 425; Tonsillar Concretions/Tonsilloliths 426; Intratonsillar Abscess 427; Tonsillar Cyst 427; Keratosis Pharyngitis 427; Diseases of Lingual Tonsils 427; Chronic Adenotonsillar Hypertrophy 427; Adenoid Facies and Craniofacial Growth Abnormalities 428; Obstructive Sleep Apnea 428 40. Malignant Tumors of Hypopharynx 449 Risk Factors 449; Pathology 450; Clinical Features 450; Diagnosis 450; Staging 450; Management 450; Carcinoma Pyriform Sinus 451; Carcinoma Postcricoid 452; Carcinoma Posterior Pharyngeal Wall 453 44. Malignant Tumors of Larynx 501 Risk Factors 501; Evaluation 502; Staging 503; Management 504; Glottic Cancer 505; Supraglottic Cancer 506; Subglottic Cancer 507; Verrucous Carcinoma 507; Organ Preservation Therapy 507; Photodynamic Therapy 507; Post-Laryngectomy Vocal Rehabilitation 507 51. Management of impaired Airway 509 Tracheostomy/Tracheotomy 510 Cricothyrotomy (Laryngotomy or Coniotomy) 513; Percutaneous Dilational Tracheostomy 513 congenital Lesions of Larynx 514 Laryngomalacia 514; Congenital Vocal Cord Paralysis 514; Congenital Subglottic Stenosis 514; Laryngeal Web/Atresia 515; Subglottic Hemangiomas 515; Laryngoesophageal Cleft 515 foreign Bodies of Air passages 515 Laryngotracheal Trauma 517 Section 7: Neck 52. Cervical Symptoms and examination 519 Neck 519 History 519; Physical Examination 519; Diagnostic Tests 522 Thyroid Gland 523 History 523; Examination 523; Investigations 525 53. Neck Nodes, Masses and Thyroid 527 Neck Nodes and Masses 527; Thyroid Neoplasms 532 54. Middle ear and Mastoid Surgeries 547 Myringotomy and Tympanostomy Tubes (Grommet) 547; Mastoidectomy 549; Cortical Mastoidectomy 550; Radical Mastoidectomy 552; Modifed Radical Mastoidectomy 553; Tympanoplasty 553 56. Operations of Nose and Paranasal Sinuses 557 Sinus operations 557 Preoperative Assessment 557; Diagnostic Nasal Endoscopy (Sinuscopy) 558; Endoscopic Sinus Surgery 559; Antral Puncture or Proof Puncture 561; Inferior Meatal Antrostomy 562; Caldwell-Luc Operation 562 Surgery of Nasal Septum 563 Submucous Resection of Nasal Septum 564; Septoplasty 564; Postoperative Care 565; Complications 565 xviii 57. Adenotonsillectomy 567 Preoperative Assessment 567; Indications for Tonsillectomy 567; Indications for Adenoidectomy 568; Contraindications 568; Surgical Techniques 568; Preoperative Measures 568; Anesthesia 569; Position 569; Surgical Instruments 569; Operative Steps 569; Postoperative Care 570; Complications 571 58. Cross References Parkinsonism; Sighing Yips Yips is the name given to a task-specific focal dystonia seen in golfers hiv infection rate swaziland purchase valtrex 500mg with mastercard, especially associated with putting hiv infection and diarrhea buy valtrex with paypal. Abnormal cocontraction in yips-affected but not unaffected golfers: evidence for focal dystonia natural antiviral supplements buy valtrex visa. Yo-yo-ing is difficult to treat: approaches include dose fractionation hiv infection rates canada order valtrex online, improved drug absorption, or use of dopaminergic agonists with concurrent reduction in levodopa dosage. Cross References Akinesia; Dyskinesia; Hypokinesia 380 Z Zeitraffer Phenomenon the zeitraffer phenomenon has sometimes been described as part of the aura of migraine, in which the speed of moving objects appears to increase, even the vehicle in which the patient is driving. Zooagnosia the term zooagnosia has been used to describe a difficulty in recognizing animal faces. In one case, this deficit seemed to persist despite improvement in human face recognition, suggesting the possibility of separate systems for animal and human face recognition; however, the evidence is not compelling. In a patient with developmental prosopagnosia seen by the author, there was no subjective awareness that animals such as dogs might have faces. Nonrecogntion of familiar animals by a farmer: zooagnosia or prosopagnosia for animals. Cross References Agnosia; Prosopagnosia Zoom Effect the zoom effect is a metamorphopsia occurring as a migraine aura in which images increase and decrease in size sequentially. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. First Part Fundamental Basis of Irisdiagnosis 1 the History of Irisdiagnosis 4 2 the Divisions of the Iris 7 3 the Colour of the Iris and the Iris-layers 12 4 How do the Iris-signs Originatefi Subsequently, I received so many enquiries for a concise textbook that I published the following work, of which the second edition now appears. My main purpose has been to provide the serious beginner with an understanding of the basic concepts, so as to enable him the more easily to absorb the extensive material contained in the works of Dr. This second edition enables me to include the results of research and experience gained over the past few years. It is my hope that further investigation will succeed in establishing a single uniform schema. Consequently, many enquiries were received for a brief textbook of the fundamental principles of Irisdiagnosis. Since the older original texts are now out of print, and difficult to obtain second hand, I therefore decided to publish the present work. The book will provide the beginner with a concise presentation of the material contained in the works of Dr. The basic iris-schema used conforms strictly to the system of Frau Eva Flink, and although this does not agree with other systems in all respects, yet the dissimilarities can be reconciled. I hope that a later generation will succeed in establishing a single uniform system. So much the more so since the opportunity is thus provided to include in the text the experience of more recent years. I hope that the edition will help to stimulate the exchange of knowledge and experience among iris investigators all over the world, as well as to provide a basic text for those interested. Only so can research into the subject become increasingly more profound and successful. First Part Fundamental Basis of Irisdiagnosis Chapter 1 the History of Irisdiagnosis Before commencing the study of Irisdiagnosis, it is necessary to clarify two terms which are always being confused: Iris-diagnosis and Eye-diagnosis. Irisdiagnosis is the observation and diagnosis of disease from the iris, and is sometimes referred to as Iriscopy. Eye-diagnosis is the observation and diagnosis of diseases affecting the whole eye, including the pupil and iris, and the immediately surrounding parts. References to it are found in the works of Hippocrates, as also in the Medical School of Salerno, and in Philostratus. The first reference to it by a physician of more recent times is found in the work of Philippus Meyens. In his book Chiromatica medica, published in Dresden in 1670, he draws attention to the signs in the iris and their interpretation. Since the stomach has a close relationship to it, then all diseases originating in the stomach are found in the eyes. The right side of the eyes shows the state of all organs inside the body which lie on the right side, such as the liver, the right thorax and the blood vessels. The left side of the eyes can show all organs which lie on the left side, therefore the heart, left thorax, spleen and small blood vessels. Conditions of health and disease arising from the heart are found here, especially weakness of the heart or fainting. The lowest part of the eyes represents the genitalia and also kidneys and bowels, from which colic, jaundice, stone, diseases of the gall and venereal diseases are to be found. If the eyes have far too many lines and 6 flecks they signify a state of unhealth in respect of the whole body. In 1786, Christian Haertels published in Gottingen a dissertation under the title De oculo et signo (The eye and its signs). Even though the significance of the eye was acknowledged in olden times, and special attention directed to it, nevertheless almost all these works refer even more to the Symptomatology. The complete examination, comprising inspection of the urine, diagnosis from the hand, nails and facies, assessment of hereditary taints, and diagnosis from the tongue, are neither taught nor acknowledged today in the technical colleges, with the exception of urine analysis where there is some acceptance. However, it is very important to remember that up to the beginning of the nineteenth century, such methods were an important part of orthodox medicine. The true discoverer of Irisdiagnosis in its present form was the Hungarian physician-Dr. In the year 1881 he published the method in his workDiscoveries in the field of Natural Science and Medicine: Instruction in the study of Diagnosis from the Eye. On the basis of several decades of comparative study, von Peczely taught that certain indications in the iris were to be related to organic diseases, and that from the localisation of such a sign conclusions could be drawn as to the disease of the corresponding organ. The head and thorax are shown correspondingly in the upper half of the iris; the arms, abdominal organs and legs in the lower half of the iris. The whole area inside the iris-wreath is correlated with the gastro-intestinal tract, showing the ascending colon in the right iris, the transverse colon in both irides, and the descending colon (including sigmoid and ampulla) in the left iris. The book consisted of 284 pages, and an atlas with 258 monochrome and 12 coloured double-iris drawings. From about the year 1887, the Tubingen ophthalmologist Schlegel supported Irisdiagnosis. The names of others who were prominent at the turn of the century should be mentioned: Stiegele, Rapp, Wirtz, Zoepperitz. However, these well-known names are superseded in significance by that of Pastor Felke (1856-1926), to whom the credit belongs for complete originality in this field. His eye-diagnosis, upon which he himself unfortunately never wrote, has been expounded by 7 A. Even after his death, Felke influenced the development of Irisdiagnosis through his pupils, whose influence is still evident today. Hense, as well as Frau Pastor Madaus and her daughter, Eva Flink, together with many other indirect pupils. The list may be concluded with the names of Angerer, Baumhauer, Deck, Kronenberger, Struck, Dr. Much is still to be done, and many pages have yet to be added to the history of Irisdiagnosis. Nearly every iris researcher has tried to evolve something special for himself, with the result that varying perceptions and interpretations are current. These differences are inevitable, for one investigator had no academic training, and presented his observations in the language that was familiar to him, while others had already studied medicine and made use of scientific qualifications. Some considered the colour changes more (Liljequist), while others were chiefly concerned with the location of signs (Peczely). It should also not be forgotten that many signs may appear according to the locality, and in consequence of nutritional and climatic influences. This book will endeavour to present the best, the most useful, and generally considered most important information from all systems. If one wishes to commence something it is usual to make a plan, either on paper or at least in the head. The hourly division 1 12 is indeed familiar to everyone, but is rather crude for the precise location of iris signs, whereas the radial division into minutes 1-60 is suitable for all purposes For those who wish to keep to the degree or hourly division it will suffice but In this book, the 1-60 division will be followed. Circular division: Now note the second most important aspect of iris topography, namely, the circular division. From the pupil to the outer border of the iris the area is divided by concentric rings.

Transmitted by sexual contact antiviral medication shingles purchase valtrex with mastercard, sharing of contaminated needles and syringes hiv infection rates nigeria cheap 1000 mg valtrex with mastercard, blood transfusion antiviral xl3 order valtrex from india, as well as vertical transmission from mother to child including breast-feeding 3 antiviral yeast infection discount valtrex 1000mg with mastercard. Children with an infected mother (intrauterine/ peripartum transmission, breast feeding) C. Most patients with anterior uveitis or intermediate uveitis respond to therapy with corticosteroids a. Patients with retinal vasculitis typically respond to therapy with periocular or systemic corticosteroids 3. Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma with opportunistic eye infections or malignant cell infiltration a. Patients should be counseled about the risks of transmission and urged to practice safe sex (including the use of condoms). Additionally, infected women should be counseled about pregnancy and the avoidance of breastfeeding Additional Resources 1. Ocular histoplasmosis syndrome is believed to be due to exposure to Histoplasma capsulatum via the respiratory tract a. The organism may then spread through the bloodstream from the lungs to the choroid 2. This condition occurs most frequently in patients who live near the Ohio River and Mississippi River valley areas and watershed areas 2. Atrophic "punched-out" round or streak-shaped scars often prominent in retinal periphery 2. Absence of vitreous cells although choroidal inflammation without vitreous cells or choroidal neovascularization may occur (in primarily acquired disease) and cause vision loss in immunocompetent patients 5. In rare cases immunocompromised patients exposed to the fungal pathogen may develop a. Bevacizumab (Avastin), pegaptanib sodium (Macugen), ranibizumab (Lucentis) intravitreal injection b. Rarely large lesions with poor vision and extrafoveal vascular ingrowth sites may be amenable to subfoveal surgery V. Intravitreal triamcinolone: glaucoma, cataract, endophthalmitis (infectious, sterile) C. Ocular photodynamic therapy with verteporfin for choroidal neovascularization secondary to ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome: update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, and photodynamic antiangiogenic, and surgical therapies. Differentiation between presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome and multifocal choroiditis with panuveitis based on morphology of photographed fundus lesions and fluorescein angiography. Submacular surgery for subfoveal choroidal neovascular membranes in patients with presumed ocular histoplasmosis. Managing recurrent neovascularization after subfoveal surgery in presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Exists as inactive scars, latent infection encysted in host cells at borders of scars, or active replicating infection 3. Infective forms are oocysts (soil forms which are ingested) and tachyzoites (metabolically active and antigenic organism) a. Acquired disease in postnatal period is more common than previously appreciated c. Thought to occur only if mother acquires infection for the first time while pregnant 5. Exposure to undercooked meats from infected animals, which in turn were exposed to material fecally contaminated by cats 3. Atypical forms of extensive chorioretinitis can occur in immunocompromised individuals. Active chorioretinitis is yellow-white, slightly elevated, with a relatively well-defined border 2. Variably present i) Often arteritis, but also periphlebitis ii) May be remote from the chorioretinitis d. Intracellular cysts containing bradyzoites are found at the border of healed lesions b. Retinal necrosis ensues from active disease with granulomatous inflammation in the choroid. Healed lesions show destruction of retina, retinal pigment epithelium, and choroid with variable hyperpigmentation E. High sensitivity and low specificity because of high prevalence of positive antibody titers in general population (a positive serology does not make the diagnosis but only confirms exposure) b. Immunoglobulin (Ig) M antibody determinations helpful in the diagnosis of acquired toxoplasmosis 3. Determination of toxoplasmosis IgG or IgA antibody titers in aqueous humor useful in cases with atypical features 4. Intraocular surgery such as cataract surgery or instrumentation of glaucoma filtering blebs 2. Decision to treat based on proximity to macula and optic nerve, amount of inflammation, and vision 1. Antibiotic treatment there are no studies to suggest that one therapy is more effective than another 1. Can be combined with sulfadiazine or triple-sulfa, azithromycin, or clindamycin ii. Duration of Therapy There are no specific guidelines on duration of antibiotic therapy but duration is tailored to response and requires a minimum of 4-6 weeks of systemic antibiotics C. Topical corticosteroids in patients with significant anterior chamber reaction 2. Not given alone because of risk of worsened infection without antibiotic coverage d. Periocular corticosteroids felt to be contraindicated by many experts because of reports of uncontrolled infection after injection. Discoloration of tooth enamel in children < 11 years or in babies of treated mothers E. If infection was acquired, try to prevent infection in family and neighbors by finding the source C. If pregnant and the infection is newly acquired, take antibiotic treatment to reduce risk of severe fetal effects D. If pregnant and chorioretinitis is recurrent from prior disease, treatment is for maternal indications only E. Take all medications as instructed for the length of time indicated Additional Resources 1. The effect of long-term intermittent trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole treatment on recurrences of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Infestation of the retina/choroid/vitreous with a second stage larva of Toxocara canis or Toxocara catis 2. Infestation is presumed to occur after ingestion or cutaneous infection with hematogenous spread to the eye B. More common in subtropical or tropical climates where the ground does not freeze 6. Focal, elevated, white, peripheral nodule with variable degrees of surrounding peripheral membranes and pigmentary scarring ii. Focal, elevated, white nodule, usually < 1-disc diameter, with variable pigmentation ii. Ascribed to death of the parasite with a secondary exuberant inflammatory reaction E. Contact with soil or food contaminated with feces from infected animals (dogs and cats) E. Pars planitis (peripheral granuloma or endophthalmitic forms of ocular toxocariasis) D. Parasite is assumed to be dead when the patient presents with either cicatricial or acute inflammatory changes. Treatment with albendazole or thiabendazole is of unclear benefit for eye disease a. Diagnostic biopsy of vitreous (cytology for eosinophils, anti-Toxocara antibodies) 2. Treat by controlling inflammation and following patching schedule appropriate for age E.

In to occur due to disorders affecting the small pial vessels most cases stages of hiv infection timeline purchase cheap valtrex on line, whatever be the underlying aetiology antiviral in a sentence buy valtrex us, the pathowhich supply the intraorbital portion of the optic nerve genesis of optic neuritis is presumed to be demyelination in away from the eyeball hiv infection rates state buy valtrex 1000 mg lowest price. The commonest associated cause is a demyelinating disorder of the nerve as occurs in other tracts of the white Clinical Features matter of the central nervous system (multiple sclerosis) xl3 accion antiviral valtrex 1000 mg without a prescription. Vision loss with an afferent pupillary defect may be the the occurrence of retrobulbar neuritis should always arouse only clinical feature. ElOther diseases of the central nervous system in which derly people with compromised circulation may be more optic neuritis occurs are neuromyelitis optica (of Devic), Chapter | 22 Diseases of the Optic Nerve 359 meninges, sinuses or orbit. Meningitis may affect the nerve, primarily causing a perineuritis, as may be seen in both syphilis and tuberDemyelinating disorders culosis. Sinusitis, particularly of the sphenoid and ethmoid, l Isolated and orbital cellulitis may act similarly. Parasitic infestation l Associated with multiple sclerosis by cysticercosis in the orbit or within the optic nerve is l Neuromyelitis optica another cause. Associated with infections Endogenous infections may also produce an optic neuLocal ritis; these include acute infective diseases such as infuenza, malaria, measles, mumps, chicken pox and infectious l Endophthalmitis l Orbital cellulitis mononucleosis. Systemic granulomatous infammations l Sinusitis such as tuberculosis, syphilis, sarcoidosis, toxoplasmosis l Contiguous spread from meninges, brain, base of skull and fungal infections such as cryptococcosis have also been Systemic known to cause optic neuritis. Immune-mediated disorders Here the appearance of the fundus may be typical with a white lumpy swelling of the optic nerve head and the loss Local of vision may vary from no loss to severe loss. Optic nerve inl Sympathetic ophthalmitis volvement could either be isolated or combined with ocular Systemic or central nervous system involvement. The effect of exogenous toxins is discussed under the heading of toxic optic neuropathy. The importance of a Metabolic disorders careful history and thorough systemic and ophthalmic exl Diabetes amination cannot be overemphasized in evaluating a patient l Anaemia with optic neuritis. This will help in arriving at a clinical diagnosis and avoid unnecessary, elaborate and expensive *In children it is not unusual for bilateral neuritis with disc swelling to follow viral illnesses. The more important several months and is ultimately usually restored to 6/6 of these are discussed in Chapter 31 but one condition (20/20). More detailed inspection, however, Optic neuritis due to local or systemic infections or other will show that although the pupil of the affected eye reacts disorders will have similar visual symptoms but will differ to light, the contraction is not maintained under bright ilin their clinical course and have other associated symptoms lumination so that instead of remaining contracted the pupil and signs in accordance with the underlying disease. Marcus Gunn pupil is of greater diagnostic signifcance, indicating a defect in the afferent limb of the pupillary light Symptoms refex due to a pathological lesion in the optic nerve. The predominant symptom in a patient suffering from optic the feld defects may be relative or absolute for colours. It may be infamed with involvement of the neighbouring the visual loss can be subtle or profound (there may retina showing a stellate pattern of retinal exudates in neuroeven be complete blindness in a few patients); it is usually retinitis (Fig. The tenderness of later the margins become blurred, swelling and oedema the eyeball on digital pressure is limited to a small area corensue which spread onto the retina, the retinal veins become responding roughly with the site of attachment of the superior rectus tendon. This is present only in the early stages of the disease and disappears in a few days. The visual impairment is accompanied by disturbance of other visual functions such as loss of colour vision (typically red desaturation) and reduced perception of light intensity. There may be other associated symptoms such as a history of an antecedent infuenza-like viral illness or focal neurological symptoms such as weakness, numbness and tingling in the extremities. Occasionally, patients may observe an altered perception of moving objects (Pulfrich phenomenon) or a worsening of symptoms with exercise or an increase in body temperature (Uhthoff sign). Chapter | 22 Diseases of the Optic Nerve 361 make a diagnosis of optic neuritis in patients above 50 years of age and look for evidence of ischaemic optic neuritis or other disorders. Pupillary reactions demonstrate a prominent relative scan helps in predicting the likelihood of multiple sclerosis afferent pupillary defect. The which are in the retinal nerve fbre layer and usually radiprimary disease. Typical cases which are idiopathic or Acute retrobulbar neuritis produces no ophthalmoproven to be due to demyelination are known to recover scopically visible changes, unless the lesion is near the spontaneously, slowly over time, with restoration of normal lamina cribrosa when some signs of papillitis may be seen vision, including the visual feld, though some residual with distension of the veins and attenuation of the arteries. If atrophic changes follow, the degeneration extends not General guidelines for treatment are based on a major only towards the brain but also towards the eye. In milder multicentre trial (the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial cases, pallor of the disc may be limited to the temporal side. Optic Atrophy this treatment hastens visual recovery and decreases the likelihood of recurrence, though the long-term visual this term is usually applied to the condition of the disc foloutcome is no different from that achieved by observalowing degeneration of the optic nerve. It has been pointed tion alone, because spontaneous recovery occurs in the out that injury to the nerve fbres in any part of their course natural course in most cases. Optic atrophy therefore follows extenment, particularly in severe and bilater ally affected sive disease of the retina from destruction of the ganglion cases. Oral prednisolone, in conventional doses of 1 mg/ cells, as in pigmentary retinal dystrophy or occlusion of the kg/day, should never be used alone as the recurrence rate central artery; these cases are sometimes called consecutive has been found to be significantly higher following this optic atrophy. If a patient has already been diagnosed to have multiple occurring in papillitis, neuroretinitis or papilloedema. It also follows destruction of the nerve in the orbit, recovery is specifically required. In addition, there are some conditions in which optic atrophy occurs without local disturbances but associParasitic Infestations of the Optic Nerve ated with general disease usually of the central nervous Cysticercus cellulosae within the optic nerve is rare. Such cases have a similar clinical appearance of a may mimic optic neuritis, papillitis, neuroretinitis or unichalky white optic nerve head with well-defned margins lateral severe disc oedema (Fig. The fourth type of is often mistaken for an optic nerve tumour on neuroimagatrophy is accompanied by enlargement and excavation of ing, the diagnosis is often delayed or missed. When the atrophy is due to disease or poisoning of the secTreatment includes the use of high doses of steroids to ond visual neurone proximal to the disc, so that there are no reduce infammation as the toxins released by the dying ophthalmoscopic evidences of previous local infammation, parasite are believed to be responsible for the visual loss. Medical treatment with oral albendazole and surgical rethe most common cause is multiple sclerosis, in which moval of the cyst have been tried with poor results. There is no retraction of the lamina cribrosa and the vessels increasing degree of atrophy, but in this disease it is rarely are only slightly contracted. Other causes are the various diseases Secondary atrophy, also called post-neuritic atrophy, already mentioned in the aetiology of optic neuritis, Leber has a slightly different ophthalmoscopic picture as comdisease, compressive space-occupying lesions in the orbit pared to the primary variety, and follows an injury or direct or cranium that compress the optic nerve or chiasma and pressure affecting the visual nerve fbres in any part of their the many exogenous poisons which give rise to toxic course from the lamina cribrosa to the geniculate body. The differentiation does not indicate the the nerve fbres commencing in the optic nerve near the nature or site of the pressure; it merely differentiates whether chiasma. Tabetic optic atrophy is slowly progressive and the atrophy has affected a normal disc or one which has been the prognosis is bad, but with the availability of effective choked. The characteristic ophthalmoscopic picture of postantisyphilitic treatment, the disease has now become neuritic atrophy has already been described. The same applies to the atrophy of general In the consecutive atrophy of retinal and choroidal disparalysis. The disc is always pale, but may show a variety of tints, especially associated with different types of atrophy. The pallor affects the whole disc and must be carefully distinguished from the white centre, often encroaching upon the temporal side, due to physiological cupping. The pallor is not due to atrophy of the nerve fbres, but to loss of vascularity, secondary to obliteration of the vessels; it is thus an uncertain guide to visual capacity. In primary atrophy the disc is grey or white, sometimes with a greenish or bluish tint (Fig. Stippling of the lamina cribrosa is seen; the edges are sharply defned and the surrounding retina looks normal. Owing to the degeneration of the nerve fbres there is slight cupping (atrophic cupping) which must be carefully distinguished from glaucomatous cupping. They are present normally but enlarge and beIn total optic atrophy the pupils are dilated and do not come visible only when there is a compressive obstruction to respond to light, and the patient is blind; when unilateral, venous drainage by a tumour compressing the optic nerve. Discount valtrex 1000 mg with amex. More HIV-infected individuals coming out to seek treatment. |