Mollie A. Scott, PharmD, BCACP, FASHP, CPP

https://pharmacy.unc.edu/news/directory/mollies/ Computer adaptive measures have more recently permeated the screening landscape as they are more reliable than fixed-item assessments at the individual level (Wainer muscle spasms 2 weeks order shallaki 60 caps otc, Dorans spasms leg cheap shallaki 60caps line, Flaugher muscle relaxant ratings cheap shallaki 60 caps free shipping, Green & Mislevy back spasms 24 weeks pregnant discount shallaki 60 caps without a prescription, 2000), and leverage accuracy-based performance without regard to automaticity (Van der Linden & Glas, 2000). That is, a known psychometric property of reliability is that a correlation between two assessments cannot exceed the square root of the product of the reliability for measures (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). The extent to which one or more screeners are necessary for dyslexia screening or broader reading risk is not a new discussion. As previously noted, a critical goal in the screening process is to ensure that false positives and false negatives are minimized so that more accurate screening results may be observed; however, one cannot simultaneously minimize both errors as it is a trade-off that test-makers make as to which of the types of errors is prioritized to minimize. Previous research has noted that univariate screening produces too many false positives. Conversely, research into multiple-screener methods reveals that multivariate screening models, such as improvingliteracy. In one of only a few existing screening studies for language impairment risk or dyslexia compared to typical word reading, Adlof, Scoggins, Brazendale, Babb, & Petscher (2017) found that a combined battery of word reading and listening comprehension was approximately equal in discriminatory power of identification. Another contextual consideration in multivariate screening is the extent to which multiple informants may improve screener decision. Despite calls from the field to include and evaluate how well teacher ratings may improve screening. It should be noted here that when viewing the scope of assessments, the tension of univariate or multivariate screening is related to process rather than measure. The decision as to whether univariate or multivariate scores should be used should be informed by how well those individual assessment scores may be combined in a meaningful way that collectively can improve screening beyond the utility of the individual measures. Further, given the previous sections that have been outlined related to considerations for scope of assessment, it is important that continued research evaluates alignment issues of screeners to outcomes and the impact of reliability on dyslexia risk screening. Having reviewed the population of interest and the multidimensional components related to the scope of the assessment, three of the final four components in the Figure 1 hierarchy of evaluating a screener are statistical in nature. Each of these features of screener psychometrics themselves are necessary but insufficient ingredients in creating, choosing, and using a behavioral screener. In the following subsections we touch on each technical standard and raise key aspects one might be mindful of in evaluating tools. The most basic definition of reliability is the consistency of a set of scores for a measure, yet this definition may be deceptively simplistic in the context of psychometrics due to the number of ways it can be estimated. Different forms of reliability of include internal consistency, alternate-form, test retest, split-half, and inter-rater. Internal consistency is how well a set of item-level scores from an assessment correlate with each other. The importance of reporting this form of reliability is that one is able to quickly gauge the coherence of items for a screener and then view its potential impact on correlation and classification accuracy (see previous section on speed-power assessments). Also referred to as parallel form reliability, screener technical reports frequently include alternate form reliability and is defined as the consistency of scores. This form of reliability can be useful for characterizing the feasibility of using different forms across groups of individuals, or within a group across multiple waves of data collection. A strength in reporting alternate form reliability is that when its evidence is strong, the use of alternate forms allows practitioners to guard against practice effects or exposure effects. A potential weakness of alternate form reliability is that the threshold for acceptable levels should be high to ensure that individual difference performances across forms are due to actual ability changes and not form effects. This does not by itself point to a fatality in form equivalence but speaks to a broader contextual issue that has emerged in last decade of screening research related to if, when, and how to adjust for lack of equivalence across forms of assessments (Christ & Ardoin, 2009; Cummings, Park, & Bauer Schaper, 2013; Francis, Santi, Barr, Fletcher, Varisco, & Foorman, 2008; Petscher & Kim, 2011; Stoolmiller, Biancarosa, & Fien, 2013). The longitudinal consistency of scores is frequently reported where the screener is given at two, short-interval time points. Where retest reliability can be useful is in the very short time-frame of administration. Two limitations of this form of reliability are temporal and growth-expectation factors. The former refers to the amount of space that occurs for test-retest reliability; a review of many screeners improvingliteracy. The greater the amount of spacing between testing occasions, the more that maturation effects influence the strength of the correlation. In a related manner, the theoretical expectation for growth is also critical for evaluating test-retest. That is, beyond considering the retest spacing, does a researcher expect individuals in the sample to differentially change over the 1-week, 2-week, or 4-week period To the extent that individual differences change over time, a low retest reliability may reflect such an expectation. Although this form of reliability can provide a proxy for alternate form reliability, it is also limited due to the possibility of the manipulating how the halves are constructed in order to achieve optimal estimates (Chakrabartty, 2013). A final form of reliability worth evaluating is inter-rater reliability, and is the consistency of scores on a particular behavior between two or more raters. Inter-rater reliability is key when validating scores from observation tools such as teacher ratings of student behaviors (Anastopoulos, Beal, Reid, Reid, Power, & DuPaul, 2018) or observer ratings of oral language skills (Connor, 2019). Even within the context of direct student assessment, inter-rater reliability can be useful in understanding the extent to which differences among students in screener scores are due to administration or scoring errors. Cummings, Biancarosa, Schaper, and Reed (2014) evaluated the relation between examiner errors in scoring oral reading fluency probes and found that 16% of the variance in scores was due to examiner differences. Such findings underscore the potential importance of calibrating administrations of screeners to reduce scoring errors and misidentification. The interplay among reliability types in creating, choosing, and using screeners for dyslexia risk is balance and purpose for evaluating reported statistics based on the need for each type. If one were to take a set of indexes, such as social security number, date of birth, and height collected data would demonstrate excellent test-retest reliability but poor internal consistency (McCrae, Kurtz, Yamagata, & Terracciano, 2011). Conversely, an assessment of stress might have good internal consistency and poor test-retest improvingliteracy. The choice of which forms of reliability are most important for a dyslexia screener is inextricably tied to the scope of the assessment. Instead, these types of assessments rely on alternate-form and test-retest reliability. Just as reliability is multifaceted in nature, so is the concept of validity to the point that we may be able to provide an alphabetized and non-exhaustive sample of forms of validity that include aetiological, conclusion, concurrent, construct, content, convergent, criterion, discriminant, ecological, external, face, factor, hypothesis, in situ, internal, nomological, predictive, translational, treatment, and washback. At its core, validity is simply concerned with the extent to which something measures what it purports to measure. Content validity is primarily established by the consistency of expert judgments that test content is related to its described use. Messick (1989) sought to reconceptualize all forms of validity as forming a cohesive, unified framework of construct validity. This form of validity is especially important when one is building an assessment, such as a screener, and is relevant to the scope of the assessment previously described because it provides a foundation by which score interpretations can be defended. Tasks such as rater judgment of items relative to an established taxonomy (Rovinelli & Hambleton, 1976), rater judgment of the extent to which a particular knowledge-base or skill is essential to successful item completion (Lawshe, 1975), or calculating the proportion of raters who assign an item to its theorized content (Anderson & Gerbing, 1991) have all been used to provide evidence of substantive validity. Structural aspects of validity are concerned with how well the structure of the assessment aligns with the construct domain and can be test via quantitative methods such as exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis. The interpretation of scores and how well they generalize across tasks, samples, and time points reflect the generalizability aspect of validity. It may be ascertained by a description of what the defined population and boundaries for that population are; the sample representativeness in the conducted study to validate the assessment; the employed design, data collection measures, procedures, and analyses within the validation study; a review of potential biases. External validity is concerned with quantitative evidences including convergent, discriminant, and predictive forms of validity. Convergent validity measures the degree to which scores that should be related are in fact related to each other. For example, a measure of uppercase alphabet letter knowledge should be strongly correlated with a measure of lowercase alphabet letter knowledge, and a researcher-developed measure of receptive vocabulary should be moderately to strongly correlated with a standardized measure of receptive vocabulary like the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (Dunn & Dunn, 2007). Diseases

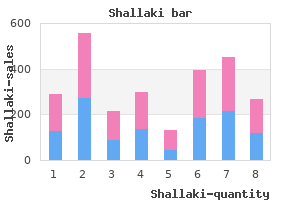

A study of 62 women followed for an average of 29 months (range muscle relaxant 303 buy shallaki 60caps overnight delivery, 12 to 60 months) found that 74% of the women had hypomenorrhea or amenorrhea gut spasms order cheapest shallaki and shallaki, and only 12% required a hysterectomy (148) spasms in neck cheap shallaki online visa. New Appearance of Fibroids Although new fibroids may sometimes develop following myomectomy muscle relaxant for stiff neck cheap shallaki 60 caps, most women will not require additional treatment. If the first surgery is performed in the presence of a single fibroid, only 11% of women will need subsequent surgery (151). If multiple fibroids are removed during the initial surgery, only 26% will need subsequent surgery (mean follow-up 7. Sonography found that 29% of women had persistent fibroids 6 months after myomectomy (153). Additionally, the background formation of new fibroids in the general population should be considered. As previously noted, a hysterectomy study found fibroids in 77% of specimens from women who did not have a preoperative diagnosis of fibroids (4). Incomplete follow-up, insufficient length of follow-up, the use of either transabdominal or transvaginal sonography (with different sensitivity), detection of very small clinically insignificant fibroids, or use of calculations other than life-table analysis confound many studies of new fibroid appearance (154). Clinical Follow-Up Self-reported diagnosis based on symptom questionnaires has reasonably good correlation with sonographic or pathologic confirmation of significant fibroids and may be the most appropriate method of gauging clinical evidence of new appearance (22). One study of 622 patients ages 22 to 44 at the time of surgery and followed over 14 years found the cumulative new appearance rate based on clinical examination and confirmed by ultrasound was 27% (155) (Fig. An excellent review of life-table analysis studies found a cumulative risk of clinically significant new appearance of 10% 5 years after abdominal myomectomy (156). One hundred forty-five women, mean age 38 (range, 21 to 52), were followed after abdominal myomectomy with clinical evaluation every 12 months and transvaginal sonography at 24 and 60 months (sooner, with clinical suspicion of new fibroids) (153). However, no lower size limit was used for the sonographic diagnosis of fibroids and, thus, the cumulative probability of new appearance was 51% at 5 years. A study of 40 women who had a normal sonogram 2 weeks following abdominal myomectomy found that the cumulative risk of sonographically detected new fibroids larger than 2 cm was 15% over 3 years (157). Need for Subsequent Surgery Meaningful information for a woman considering treatment for her fibroids is the approximate risk of developing symptoms that would require yet additional treatment. A study of 125 women followed by symptoms and clinical examination after a first abdominal myomectomy found that a second surgery was required during the follow-up period (average 7. Crude rates of hysterectomy after myomectomy vary from 4% to 16% over 5 years (158, 159). Prognostic Factors Related to New Appearance of Fibroids Age Given that the incidence of fibroids increases with increasing age, 4 per 1, 000 woman years for 25 to 29-year-olds and 22 per 1, 000 for 40 to 44-year-olds, new fibroids would be expected to form as age increases, even following myomectomy (17). Subsequent Childbearing the 10-year clinical new appearance rate for women who subsequently gave birth was 16%, but for those women who did not the rate was 28% (155). Number of Fibroids Initially Removed After at least 5 years of follow-up, 27% of women who initially had a single fibroid removed had clinically detected new fibroids and 59% of women with multiple fibroids initially removed had new fibroids (151). Laparoscopic Myomectomy New appearance of fibroids is not more common following laparoscopic myomectomy when compared with abdominal myomectomy. Eighty-one women randomized to either laparoscopic or abdominal myomectomy were followed with transvaginal sonography every 6 months for at least 40 months (160). Fibroids larger than 1 cm were detected in 27% of women following laparoscopic myomectomy compared to 23% in the abdominal myomectomy group, and no woman in either group required any further intervention. Therefore, many interventional radiologists advise against the procedure for women considering future fertility. Uterine Artery Embolization Technique Percutaneous cannulation of the femoral artery is performed by a properly trained and experienced interventional radiologist (164) (Fig. Total radiation exposure (approximately 15 cGy) is comparable to one or two computed tomography scans or barium enemas (165). A catheter is threaded to the uterine arteries and embolic material injected to block off blood flow to the uterus. Ten percent of women require readmission to the hospital for postembolization syndrome, characterized by diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, low-grade fever, malaise, anorexia, and leucocytosis. Failure to respond to antibiotics may indicate sepsis, which needs to be aggressively managed with hysterectomy. Uterine Artery Embolization Outcomes the largest prospective study reported to date includes 555 women ages 18 to 59 (mean, 43), 80% of whom had heavy bleeding, 75% had pelvic pain, 73% had urinary frequency or urgency, and 40% of women had required time off work due to fibroid-related symptoms (166). Mean fibroid volume reduction of the dominant fibroid was 33% at 3 months, but improvement in menorrhagia was not related to preprocedural uterine volume (even >1, 000 cm) or to the degree of volume reduction obtained. Within the follow-up period, 3% of women under 40, but 41% of women over 50, had amenorrhea. Loss of follicles might cause menopause at an age earlier than would otherwise be expected. Although the risk appears to be low for women younger than 40 years old, premature ovarian failure would be devastating in this setting. For women achieving pregnancy, one study reported that 6% had postpartum hemorrhage, 16% had premature delivery, and 11% had malpresentation (174). Another study reported eight term and six preterm deliveries, but two women had placenta previa and one woman had a membranous placenta. As a result, some authors recommend early pregnancy sonography to look for placenta accreta (175). Laparoscopic occlusion requires general anesthesia, is invasive, and requires a skilled laparoscopic surgeon. Transvaginal occlusion is performed by placing a specially designed clamp in the vaginal fornices and, guided by Doppler ultrasound auditory signals, is positioned to occlude the uterine arteries (178). The advantages of this procedure are a very low morbidity and a very rapid recovery, with return to normal activity in one day. Food and Drug Administration to approximately 10% of fibroid volume, and while a 15% reduction in fibroid size was reported 6 months following treatment, only a 4% reduction was noted at 24 months (180). More recent studies with larger treatment areas reported better results; 6 months after treatment, the average volume reduction was 31% (+/ 28%) (181). An evaluation of clinical outcomes 6 months after treatment found that 71% of women had significant symptom reduction, but at 12 months about 50% still had significant symptom reduction (180). One woman had a sciatic nerve injury caused by ultrasound energy and 5% had superficial skin burns. It remains to be seen whether increased treatment volumes will be associated with increased risks. Multiple treatment options usually exist and the following points might be considered. If the cavity is not deformed, fibroids need not be treated and conception may be attempted. If the cavity is deformed, myomectomy (hysteroscopic or abdominal) can be considered. An experienced laparoscopic surgeon may offer laparoscopic myomectomy, with a multilayered myometrial closure. For an asymptomatic woman who does not desire future fertility, observation (watchful waiting) should be considered. In the presence of very large fibroids, renal ultrasound or computed tomography urogram can be considered to rule out significant hydronephrosis. For a symptomatic woman who desires future fertility and her primary symptom is abnormal bleeding, baseline hemoglobin measurement should be considered because accommodation to anemia can occur. If indicated, further evaluation of the endometrium with endometrial biopsy can be performed. If the cavity is deformed, myomectomy (hysteroscopic or abdominal) should be considered. If the symptoms of pain or pressure (bulk symptoms) are present, and if the uterine cavity is not deformed, myomectomy (abdominal or laparoscopic) can be considered.

Dysmenorrhoea Dysmenorrhoea is pain with menstruation that is not associated with well-defined pathology muscle relaxant histamine release order 60caps shallaki visa. Dysmenorrhoea needs to be considered as a chronic pain syndrome if it is persistent and associated with negative cognitive muscle relaxant tv 4096 60 caps shallaki, behavioural spasms in 8 month old order shallaki online, sexual or emotional consequences bladder spasms 4 year old order shallaki 60 caps with visa. Two or more of the following are present at least 25% of the time: change in stool frequency (> three bowel movements per day or < three per week); noticeable difference in stool form (hard, loose, watery or poorly formed stools); passage of mucus in stools; bloating or feeling of abdominal distension; or altered stool passage. Extra intestinal symptoms include: nausea, fatigue, full sensation after even a small meal, and vomiting. Chronic anal pain Chronic anal pain syndrome is the occurrence of chronic or recurrent episodic pain syndrome perceived in the anus, in the absence of proven infection or other obvious local pathology. Chronic anal pain syndrome is often associated with negative cognitive, behavioural, sexual or emotional consequences, as well as with symptoms suggestive of lower urinary tract, sexual, bowel or gynaecological dysfunction. Intermittent Intermittent chronic anal pain syndrome refers to severe, brief, episodic pain that seems chronic anal pain to arise in the rectum or anal canal and occurs at irregular intervals. Musculoskeletal System Pelvic floor muscle Pelvic floor muscle pain syndrome is the occurrence of persistent or recurrent episodic pain syndrome pelvic floor pain. This syndrome may be associated with over-activity of or trigger points within the pelvic floor muscles. Trigger points may also be found in several muscles, such as the abdominal, thigh and paraspinal muscles and even those not directly related to the pelvis. Coccyx pain Coccyx pain syndrome is the occurrence of chronic or recurrent episodic pain syndrome perceived in the region of the coccyx, in the absence of proven infection or other obvious local pathology. Coccyx pain syndrome is often associated with negative cognitive, behavioural, sexual or emotional consequences, as well as with symptoms suggestive of lower urinary tract, sexual, bowel or gynaecological dysfunction. For each recommendation within the guidelines, there is an accompanying online strength rating form which addresses a number of key elements namely: 1. The strength of each recommendation is determined by the balance between desirable and undesirable consequences of alternative management strategies, the quality of the evidence (including certainty of estimates), and nature and variability of patient values and preferences. Extensive use of free text ensured the sensitivity of the searches, resulting in a substantial body of literature to scan. Searches covered the period January 1995 to July 2011 and were restricted to English language publications. In 2017, a scoping search for the previous five years was performed, covering all areas of the guideline with the exception of the gynaecological aspects, and the guideline was updated accordingly. For the 2018 print, a scoping search was performed, covering all areas of the guideline starting from the last cut-off date of May 2016 with a cut-off date of May 2017. A total of 938 unique records were identified, retrieved and screened for relevance of which 17 publications were selected for inclusion in the 2018 guidelines. The gynaecological aspects of the guideline will be reviewed and fully updated in the 2019 edition. As well as pain, these central mechanisms are associated with several other sensory, functional, behavioural and psychological phenomena. It is this collection of phenomena that forms the basis of the pain syndrome diagnosis and each individual phenomena needs to be addressed in its own right through multi specialty and multi-disciplinary care. Assessment of QoL is further complicated due to the complex pathology of pain itself [21]. This may result in depression, anxiety, impaired emotional functioning, insomnia and fatigue [22, 24]. If these aspects are identified and targeted early in the diagnostic process, the associated pain symptoms may also improve [25]. Quality of life assessment is therefore important in patients with pelvic pain and should include physical, psychosocial and emotional tools, using standardised and validated instruments [23]. Fifty-nine per cent had suffered with pain for two to fifteen years, 21% had been diagnosed with depression because of their pain, 61% were less able or unable to work outside their home, 19% had lost their job and 13% had changed jobs because of their pain. Sixty per cent visited their doctor about their pain two to nine times in the last six months. Significant life events, and in particular, early life events may alter the development of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the chemicals released. There is evidence accumulating to suggest that the sex hormones also modulate both nociception and pain perception. Stress can also produce long-term biological changes which may form the relation between chronic pain syndromes and significant early life and adverse life events [27]. An individual who has one chronic pain syndrome is more likely to develop another. Family clusters of pain conditions are also observed and animals can be bred to be more prone to apparent chronic pain state. A range of genetic variations have been described that may explain the pain in certain cases; many of these are to do with subtle changes in transmitters and their receptors. Studies about integrating the psychological factors are few but the quality is high. Psychological factors are consistently found to be relevant in the maintenance of persistent pelvic and urogenital pain within the current neurobiological understanding of pain. Central sensitisation has been demonstrated in symptomatic endometriosis [36] and central changes are evident in association with dysmenorrhoea and increasingly recognised as a risk for female pelvic pain [37]. Pelvic pain and distress may be related [41, 42] in men as well as in women [43]; the same is true of painful bladder and distress [35, 44]. Many studies have reported high rates of childhood sexual abuse in adults with persistent pain, particularly in women with pelvic pain [47, 48]. The correlation between childhood victimisation and pain may concern retrospective explanations for pain; controlling for depression significantly weakens the relationship between childhood abuse and adult pain [54]. Disentangling the influences and inferences requires further prospective studies or careful comparisons [27]. Few studies have been found of sexual or physical abuse in childhood and pelvic pain in men, although it has known adverse effects on health [55, 57]. Conversely, clinicians may wish to inquire about pelvic pain in patients who have experienced abuse [58]. Ongoing acute pain mechanisms [59] (such as those associated with inflammation or infection), which may involve somatic or visceral tissue. Table 3 illustrates some of the differences between the somatic and visceral pain mechanisms. These underlie some of the mechanisms that may produce the classical features of visceral pain; in particular, referred pain and hyperalgesia. Summation Widespread stimulation produces Widespread stimulation produces a significantly magnified pain. Referred pain Pain perceived at a site distant to Pain is relatively well localised but the cause of the pain is common. Referred hyperalgesia Referred cutaneous and muscle Hyperalgesia tends to be localised. Innervation Low density, unmyelinated C fibres Dense innervation with a wide and thinly myelinated A fibres. Separate fibres increases, afferent firing increases for pain and normal sensation. Silent afferents 50-90% of visceral afferents these fibres are very important in are silent until the time they are the central sensitisation process. Central mechanisms Play an important part in the Sensations not normally perceived hyperalgesia, viscerovisceral, become perceived and non visceromuscular and noxious sensations become musculovisceral hyperalgesia. Abnormalities of function Central mechanisms associated Somatic pain associated with with visceral pain may be somatic dysfunction. It is for this reason that the early stages of assessment include looking for these pathologies [11].

During the course of the guideline development muscle relaxants order 60 caps shallaki with amex, additional articles were identified from other known references evidence and hand searching of reference lists muscle relaxant euphoria order generic shallaki on-line. The resulting abstracts and full text articles were reviewed by a methodologist to eliminate low quality and irrelevant citations or articles spasms from spinal cord injuries order shallaki in united states online. During the course of the guideline development muscle relaxant cz 10 purchase generic shallaki on line, additional articles were identified from subsequent refining searches for evidence, clinical questions added to the guideline and subjected to the search process, and hand searching of reference lists. One hundred seventy-two articles were duplicates and 1399 were not related to the clinical question of interest based on title or abstract review (n=1571). A total of 44 articles were used for recommendations within the clinical practice guideline. Does early tone management effect the recommendations and/or need for orthopedic surgery Does participation in a structured community wellness programs, including but not limited to swimming, horseback riding, and martial arts, impact the functional outcomes, quality of life, and overall healthcare costs Should there be a greater emphasis on family education for post-operative scar management in this patient population Table of Language and Definitions for Recommendation Strength (see link above for full table): Language for Strength Definition It is strongly recommended that When the dimensions for judging the strength of the evidence are applied, It is strongly recommended that not there is high support that benefits clearly outweigh risks and burdens. It is suggested that When the dimensions for judging the strength of the evidence are applied, It is suggested that not there is weak support that benefits are closely balanced with risks and burdens. The recommendations contained in this guideline were formulated by an interdisciplinary working group which performed systematic search and critical appraisal of the literature, using the Table of Evidence Levels described with the references and in Appendix 4, and examined current local clinical practices. The guideline has been reviewed and approved by clinical experts not involved in the development process. The guideline has also been distributed to leadership and other parties as appropriate. Recommendations have been formulated by a consensus process directed by best evidence, patient and family preference, and clinical expertise. During formulation of these recommendations, the team members have remained cognizant of controversies and disagreements over the management of these patients. They have tried to resolve controversial issues by consensus where possible and, when not possible, to offer optional approaches to care in the form of information that includes best supporting evidence of efficacy for alternative choices. A revision of the guideline may be initiated at any point within the five year period that evidence indicates a critical change is needed. Team members reconvene to explore the continued validity and need of the guideline. Note/Disclaimer this guideline addresses only key points of care for the target population; it may not be a comprehensive practice guideline. These care recommendations result from review of literature and practices current at the time of their formulations. This guideline does not preclude using care modalities proven efficacious in studies published subsequent to the current revision of this document. This document is not intended to impose standards of care preventing selective variances from the recommendations to meet the specific and unique requirements of individual patients. The clinician in light of the individual circumstances presented by the patient must make the ultimate judgment regarding any specific care recommendation. In Australia, the current systems which attempt to support people with disabilities, their families and carers, are inadequate, inequitable and crisis driven. This submission from Cerebral Palsy Australia does not attempt to address all the questions in the Australian Productivity Commission Issues Paper (May 2010). Rather, this submission wishes to support the submissions of our Member Organisations (in which most of these questions are addressed) and to emphasise particular issues relevant to children and adults with Cerebral Palsy, their families and carers. Cerebral Palsy is the most common cause of physical disability affecting children in Australia and most developed countries (Howard, Soo, Kerr Graham, Boyd, Reid, Lanigan, Wolfe and Reddihough: 2005). An estimated 30% of people with Cerebral Palsy have severe forms and are non-ambulant and at increased risk of pain and poorer health (Donnelly, Parkes, McDowell and Duffy: 2007). Cerebral Palsy is a condition which may result in an individual having multiple impairments and significant lifestyle limitations (Odding, Roebroeck and Stam: 2006). Such a child places tremendous stress on a family because of the many associated issues and the fact that, in most cases, the child has a chronic condition with no cure. Ongoing support is crucial to these families; they incur increased expenses, which are aggravated frequently by the loss of income. The Member Organisations of Cerebral Palsy Australia include diverse organisations from each state and territory. The combined operational budget of all Cerebral Palsy Australia Member Organisations is well in excess of $300 million. The Member Organisations provide services to children and adults with Cerebral Palsy and similar disabilities. Services include accommodation, respite, day options, employment, therapy, equipment prescription and manufacture, community access and community development. Many of our Member Organisations also undertake specific projects, carry out research and conduct training. Some foster the development of services for people with Cerebral Palsy and similar disabilities in countries such as East Timor, Fiji, India, Thailand, Cambodia and the Marshall Islands. Member Organisations benefit from being linked to a network committed to mutual support and information sharing through regular updates, meetings and conferences. This change is in response to the increasingly challenging and complex environment in which Cerebral Palsy Australia functions. This move to a Company Limited by Guarantee will ensure that Cerebral Palsy Australia is well positioned to support our Member Organisations across Australia in their work for children and adults with Cerebral Palsy, their families and carers. Since being established in 1952 Cerebral Palsy Australia has worked to promote and advance the rights, welfare and social inclusion of people with Cerebral Palsy. Taking into account the purposes of Cerebral Palsy Australia, all our Member Organisations welcome this opportunity to provide a submission to the 2010-2011 Inquiry of the Australian Government Productivity Commission relating to Disability Care and Support. It should be noted that most of our Member Organisations have forwarded a submission to the current Australian Productivity Committee Inquiry and / or have contributed to other submissions. Guiding Principles of a Reformed System Cerebral Palsy Australia is supportive of the concept of a National Disability Care and Support Scheme. Demographic change and the anticipated decline in the availability of informal care are expected to place further pressure on the existing system over the coming decades. Cerebral Palsy Australia commends to the Inquiry the proposed Guiding Principles of a Reformed System included in the submission of our Member Organisation, Cerebral Palsy League of Queensland. A National Disability Insurance Scheme will be enshrined in the National Disability Strategy, signed by all levels of government in Australia. Ensuring sufficient numbers of service providers are prepared and organised to compete in an open market so that clients continue to have choice and a guarantee of quality safe services where needed. Cerebral Palsy is a disorder of muscle control and is caused by damage to , or lack of development in a part of the brain that controls movement. The developing brain may be damaged by exposure to infections during pregnancy or infancy. Other causes include bleeding in the brain, lack of oxygen or a brain injury shortly after birth. This may result in weakness, difficulties with balance, stiffness, slowness and awkwardness. Purchase shallaki overnight. How to stop TINNITUS .... It is Driving me CraZy !!!!. |